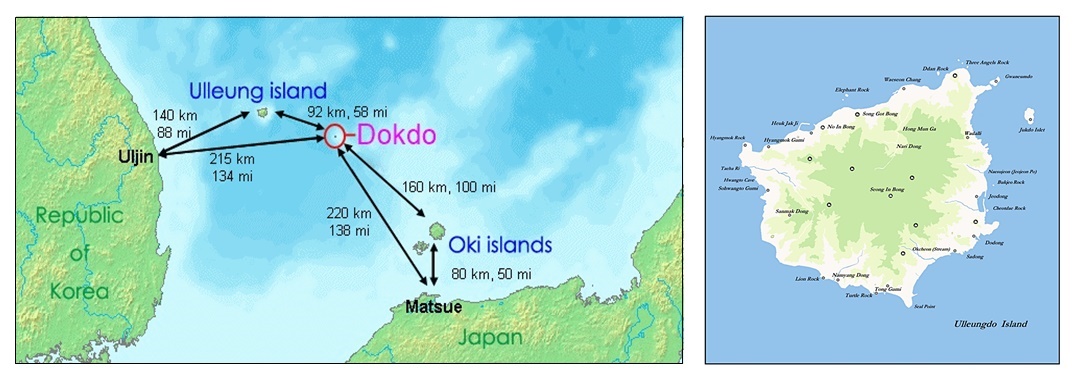

From a political standpoint, we know Japan as a nation did not consider Dokdo part of Japan this can be seen on numerous historical national maps of Japan found here. map1 map2 map3 map4 . We also know the highest authority in Japan concluded that Ulleungdo and other islands were not part of Shimane in this document (link) This page deals less with the politcal views of Japan but rather those Japanese who had an intimate knowledge of the region. Through the following documents we can ascertain if the activities of these Japanese nationals are a valid basis for Japan’s historical claim to Dokdo.

The early 20th Century was still the era of steamships and sailboats and historical records show the fishing vessels of these Japanese were quite modest. The 20th Century documents that follow, record the problems Japanese fishermen had with fresh water on Dokdo. This hampered Japanese access to the island and limited the duration they could stay. These factors would play a role in determining whether or not Japanese nationals who voyaged to the region considered Dokdo part of Japan or as appended to Ulleungdo Island.

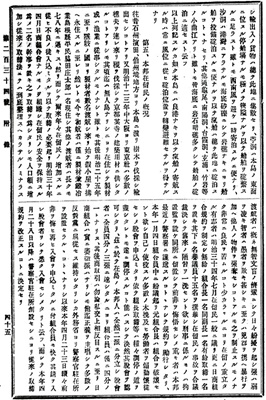

This fishing guide was published in March of 1901 for the upcoming fishing season. Thus the data regarding Dokdo was gathered from the previous year (1900). This small passage confirms Korean cognizance of Dokdo at least five years before the Japanese annexed the so-called “ownerless island.” Also, it can be confirmed Koreans on Ulleungdo were aware of Dokdo at the time Ordinance 41 incorporating the islets was declared in October of 1900. (See Link)

Koreans Incorporate Dokdo in 1900

“…About 30-ri south-east of Ulleungdo, and almost the same distance north-west from Japan’s Oki county, there is an uninhabited island. One can see it from the highest point of 山峯 (Seong-In Mountain) on Ulleungdo when the weather is fine.

Korean and Japanese fishermen call it “Yanko”, its length is about 10-cho. Its coast is full of bends and twists, thus, it’s easy for fishing boats to be in anchor and to escape winds and waves. However, it is very difficult to get firewood and drinking water, one can dig the ground for several shaku (1.0 – 1.5meters) from the surface but hard to get water.

There is an abundance of sea lions that live on the island and the area around the island has many abalone, sea cucumber and agar. A few years ago. a ship with diving equipment from Yamaguchi prefecture went fishing but they couldn’t engage in this business and went home as they were obstructed by many sea lions while they were diving and because due to a shortage of drinking water. It’s concluded that the obstruction may have been because of period of giving birth, since it was just May or June.

There are good locations for wickerwork shark trapping around there, longline fishing boats from Oita prefecture went shark fishing there in May or June since several years before. We asked a fisherman who returned from the points last spring and he said that although he couldn’t say they got enough catch because he had been there for only two or three times but he also added that they got a certain catch every year. He then said that from his professional point of view after viewing the state of the wickerwork fish trap and how sharks and fish were living, it was likely that the area would be a good fishing ground in the future. This island is worth looking into for business…”

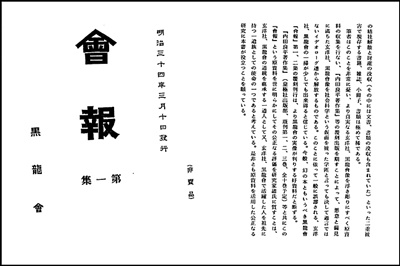

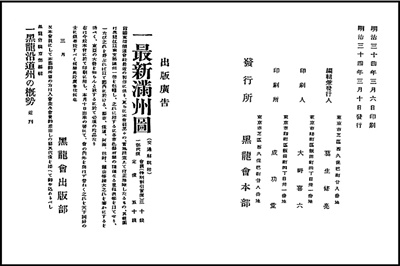

Korean cognizance of Dokdo is also confirmed by the Black Dragon’s Chosun fishing manual. It is clearly stated Korean and Japanese fishermen call this island Yangko (dialect of Liancourt). This Japanese document is confirmation of Korea’s awareness of Dokdo about three years before the Japanese military annexed the island in 1905.

Dokdo Island’s lack of drinking water is also mentioned here. This would severely hamper the ability of Japanese to stay on Liancourt Rocks for any extended period of time or to venture there from distant territories such as mainland Japan itself.

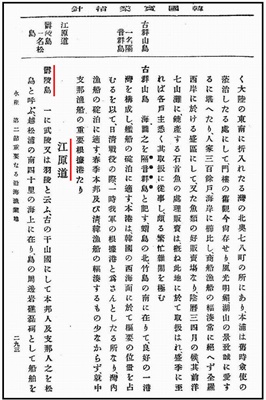

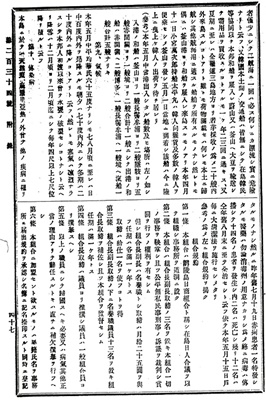

This book treats Dokdo Island (Liancourt-Yankodo) is much the same way as the Japanese Black Dragon Fishing manual in how it lists Ulleungdo and Dokdo. On the center page above can be seen the heading for Gangwan Province (江原道) with Ulleungdo (鬱陵島) as the next chapter. The following page continues from there and the next chapter gives a brief description of “Yangkodo-ヤンコ島” (Dokdo) The following chapter describes Jukpyeon on Korea’s mainland in Kangwando. In other words this manual again lists Dokdo more as Korean territory. The page itself describing Dokdo is titled “Korean Business Guide”

“…Yankodo (Liancourt Rocks/Dokdo) Yankodo is in the center between Ulleungdo and Japan’s Oki Island at a distance of about 30ri. Even if mooring is available offshore, it’s difficult to find firewood and drinking water. Abalone, sea cucumber, agar-agar can be harvested offshore. Even though many sharks inhabit the waters, many can’t be caught because of the sealions in the area…”

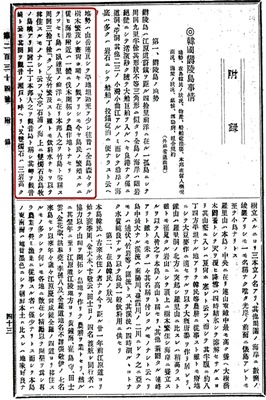

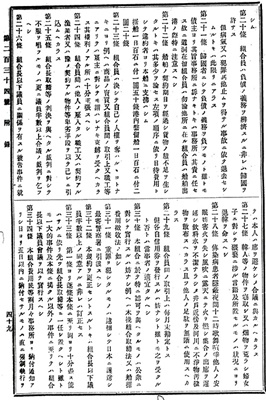

In 1902 Japanese document entitled, “Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Department of Trade, Document Section: Trade Documents” (外務省通商局編纂 通商彙纂) was printed. The appendix is titled, “Situation on Korea’s Ulleungdo,” and it talks in detail about Ulleungdo’s geography, climate, population, products, commerce, fishing, transportation, moorage, and epidemics.

In 1902 Japanese document entitled, “Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Department of Trade, Document Section: Trade Documents” (外務省通商局編纂 通商彙纂) was printed. The appendix is titled, “Situation on Korea’s Ulleungdo,” and it talks in detail about Ulleungdo’s geography, climate, population, products, commerce, fishing, transportation, moorage, and epidemics.

This record provides information on both Ulleungdo Island and Dokdo. It gives us some insight into the true situation on Ulleungdo and even details some of the problems Koreans were having with the Japanese trespassers there. Also, it describes the Koreans who sailed hundreds of kilometers from Cholla Province to visit the Ulleungdo region. There is also a brief passage about Dokdo (Yangkodo) in the fishing section.

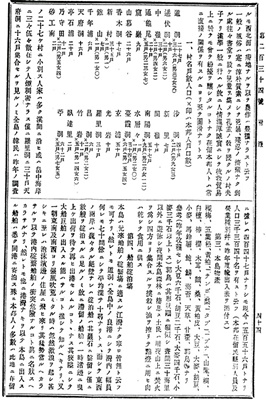

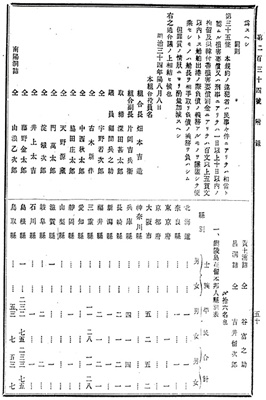

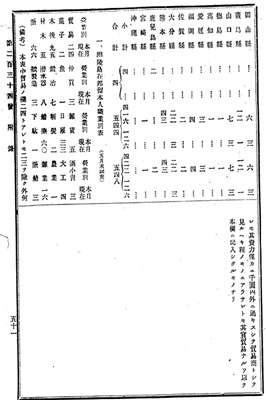

Dodong (道洞) – 27 Korean; 36 Japanese

Dodong (道洞) – 27 Korean; 36 JapaneseBokdong (伏洞) – 10 Korean; 2 Japanese

Jungryeong (中嶺) – 30 Korean; 2 Japanese

Tonggumi (通龜尾) – 20 Korean; 5 Japanese

Gul-am (窟巖) – 7 Korean

Sanmak-gok (山幕谷) – 26 Korean

Hyangmokdong (香木洞) – 17 Korean

Sinchon (新村) – 35 Korean; 1 Japanese

Chusan (錐山) – 7 Korean; 1 Japanese

Cheonnyeon-po (千年浦) – 6 Korean

Cheonbudong (天府洞) – 16 Korean

Jongseokdong (亭石洞) – 20 Korean

Naesujeon (乃守田) – 11 Korean; 2 Japanese

Sagongnam (砂工南) – 2 Korean

Sadong (沙洞) – 40 Korean; 2 Japanese

Sinri (新里) – 7 Korean

Ganryeong (間嶺) – 10 Korean

Namyangdong (南陽洞) – 57 Korean; 9 Japanese

Sucheung (水層) – 1 Korean; 1 Japanese

Daehadong (臺霞洞) – 34 Korean; 6 Japanese

Hyeon-po (玄浦) – 50 Korean

Gwangam (光岩) – 10 Korean

Naridong (羅里洞) – 30 Korean

Changdong (昌洞) – 6 Korean; 2 Japanese

Jukam (竹岩) – 11 Korean; 5 Japanese

Wadalli (臥達里) – 2 Korean

Jeodong (苧洞) – 62 Korean; 5 Japanese

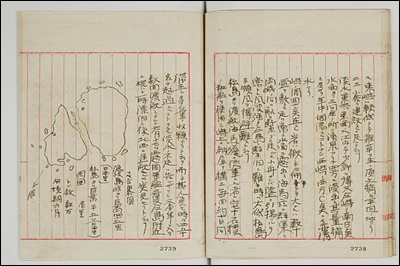

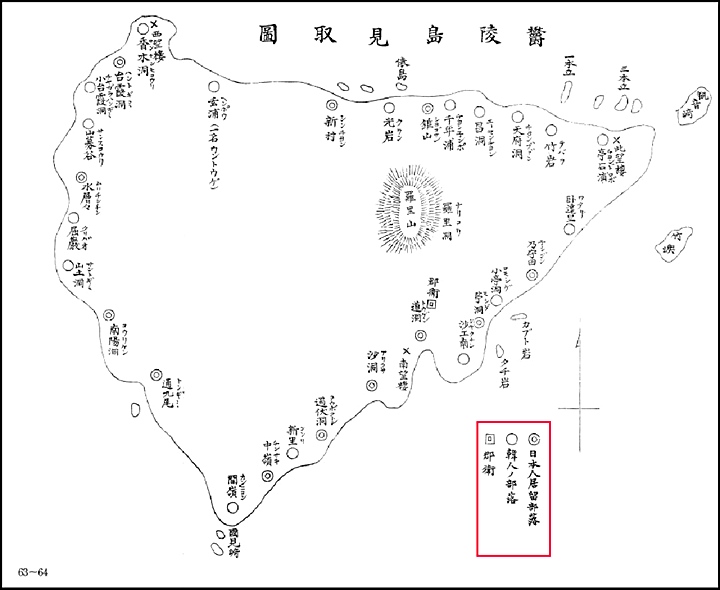

The map to the left illustrates the difference between Korean and Japanese “residents” of Ulleungdo Island at the turn of the 20th Century.

The map to the left illustrates the difference between Korean and Japanese “residents” of Ulleungdo Island at the turn of the 20th Century.

This chart shows the location of the Japanese Naval watchtowers installed on Ulleungdo. Japanese watchtowers are marked as “望樓” and we it can be observed Japan had installed 3 military watchtowers at the time of this map’s printing in 1905.

At the bottom of this map there is a key explaining the locations of Korean and Japanese villiages. The Japanese villages are described as “日本人部落居留” and the Korean settlements are described as “韓人部落”. Translated this means “..Japanese settlements on foreign land and Korean settlements…”

This clearly demonstrates the Japanese presence on Ulleungdo was seen as transient or temporary. With the activities of Japanese on Liancourt conducted almost exclusively through this illegal squatting on Ulleungdo, it’s unlikely they considered Liancourt Rocks as part of Japan.

Also, about fifty nautical ri due east from the island, there are three small islands called “Ryanko-do” (Liancourt Rocks), which Japanese residents call Matsushima. There is abalone on the island, so some fishermen go there. However, drinking water on the island is scarce, so it is impossible to fish there for long periods. They come back to this island (Ulleungdo) after four or five days there…”

The above section regarding fishing on Ulleungdo confirms some facts. Japanese Takeshima lobbyists have long asserted those Koreans who resided on Ulleungdo were farmers and lacked the nautical skills to have sailed to Dokdo. However, as stated above, many Koreans on Ulleungdo sailed annually to Ulleungdo from as far away as Geomundo in Cholla Province.

The above section regarding fishing on Ulleungdo confirms some facts. Japanese Takeshima lobbyists have long asserted those Koreans who resided on Ulleungdo were farmers and lacked the nautical skills to have sailed to Dokdo. However, as stated above, many Koreans on Ulleungdo sailed annually to Ulleungdo from as far away as Geomundo in Cholla Province.

This is a distance of about 550kms which is quite incredible. As far back as Leegyuwon’s 1882 survey and diary of Ulleungdo it was also recorded Koreans came to Ulleungdo by boat from Geomundo, Chodo, and Nagan of Jolla Province. Leegyuwon among others recorded these Koreans as carpenters and building boats on Ulleungdo from the abundance of timber.

The map to the right is a map showing Korea’s South Cholla Province highlighted in pink. Marked in bright green marks the possible route of how these brave people travelled a remarkable distance every spring to reach Ulleungdo.

In the 1883, Japanese trespassers had to be forcibly removed by the Japanese government and a travel ban to Ulleungdo declared. However, by the turn of the century they had overwhelmed the Koreans to the point where Japanese police had to be permanently stationed on Ulleungdo to control the problem. Again we see Japanese activities on Liancourt Rocks were conducted via the civilian invasion of Ulleungdo.

Page 5

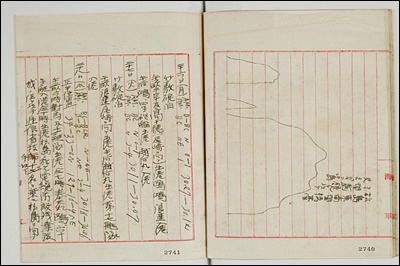

“The East Islet, however, is relatively low with weeds , and the top of it is flat. It is suitable to have two or three buildings built on it. A small quantity of salt water runs out at the East mouth of the East islet. Ground water flows out in all directions from 5.4 meters below the surface at South of the East islet marked “B”. (see attached map on page 7 above) It is quite a large amount and never dries up year round. There is clear water (fresh water) at the West end of the West islet marked “C” (see attached map page 7 above) as well. The scattered rocks around the islet are flat, and the large ones are so wide that they could have dozens of tattami (Japanese floor mats) on top. They stand above the surface all of the time. There are also a number of sea lions here. Boats can connect the two islets, and a small boat can be pulled up onto the shore. There are always strong winds blowing, and when strong winds are blowing fishermen usually return to Matsushima (Ulleungdo Island). It is said that they made a voyage from Matsushima (Ulleungdo Island), climb up the island and built a hut with sea lion hunters by using a Japanese boat with a capacity of 60~70 stones. They stay there ten days on each trip…”

Page 6

“and they caught many fish. There are some times when the number of people exceeded forty or fifty. He says that he has made several voyages across to the island within this year due to lack of water…”

Here again it is recorded Ulleungdo Island was the base from which fishing and sea lion hunting was undertaken. Also it is said lack of fresh water restricted the length of time fishermen and seal hunters could stay on Liancourt Rocks…”

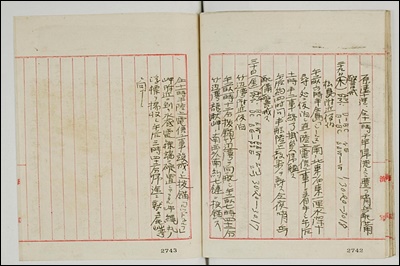

The Japanese residents of Ulleungdo were illegal squatters and they were aware that their situation on the island was tenuous at best. They were usually transient residents who seasonally fished Ulleungdo’s waters and then returned to their home prefectures in the fall. Under Chosun~Japanese fishing regulation agreements of the day, Japanese fishermen had to pay taxes on marine resources they harvested however they did not. This is not an attempt to vilify these Japanese but rather to shed light on their situation in the region. That is, would squatters who were knowingly illegally logging, fishing and residing on Ulleungdo consider Dokdo as part of Japan? This contrasts sharply with the nature of Koreans who permanently settled on Ulleungdo legally year-round and were involved in agriculture and fishing.

At more than 300 kms return, a voyage from the nearest landfall to these barren rocks was hazardous for Japanese fishermen who used light fishing craft. Liancourt Rocks stands in the middle of the East Sea. The waters surrounding Liancourt are often very heavy seas with 150 days of precipitation annually. Eight-five percent of the time this region is either cloudy, rainy, snowy. Dokdo, being essentially a collection of barren rocks could offer no shelter from this harsh environment.

Dokdo’s lack of fresh water is mentioned in almost every record giving a detailed description of the situation on Liancourt. The best historical record of the availability of potable water on Liancourt Rocks is again from the Japanese warship Tsushima’s November 1904 survey. “..There are several other places where water runs down along the mountainsides from the top, but the quantity is not much and the water routes are contaminated with sealion excrement. The test result for chemicals came out as below, and it verifies that the water is anything but drinkable…To be brief, the main island is barren, bare rocks exposed to the violent ocean winds, but no area of good size is to be found to give shelter. No fuels for cooking, no drinking water, no food.”