This page is intended to first summarize Japan’s view on the San Francisco Peace Treaty. Second, by using original documents from United State’s Department of State, Foreign Affairs Office, the reader will hopefully come away with a broader understanding of the decisions Allied Command made. This page will also show how and why the allies determined which territories were returned to post WWII Japan.

“…The negotiations involving the fate of former Japanese territories was a long, drawn-out process. The first five and seventh drafts of the treaty provided that Liancourt be given to Korea by including the islets in the Article 2(a) list. The sixth, eighth, ninth, and fourteenth drafts explicitly stated that the territory of Japan included Dokdo Takeshima. The tenth through thirteenth and fifteenth through eighteenth drafts, like the final draft, were silent on the status of Dokdo Takeshima…”

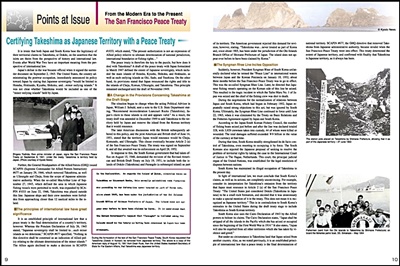

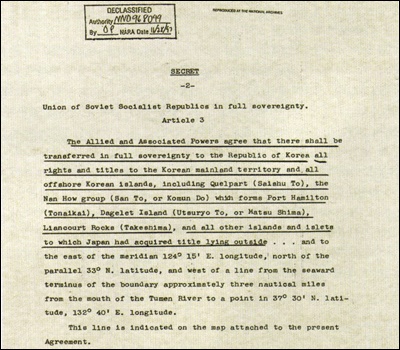

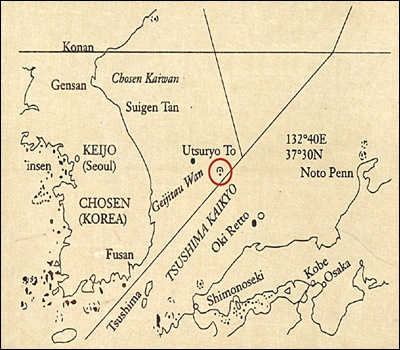

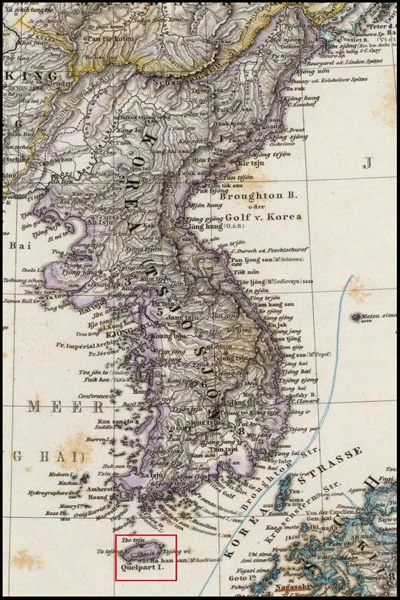

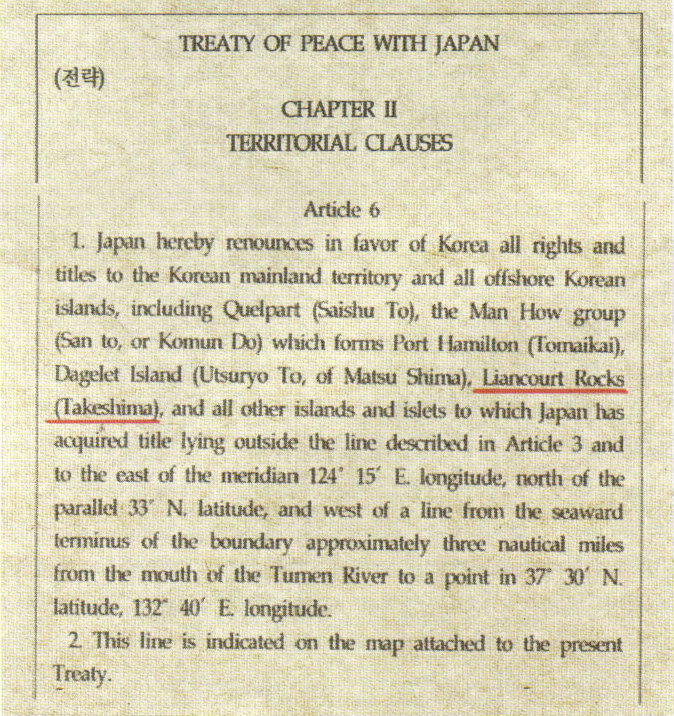

“…Article 3. The Allied and Associated Powers agree that there shall be transferred in full sovereignty to the Republic of Korea all rights and titles to the Korean Mainland territory and all offshore Korean islands, including Quelpart(Saishu To), the Nan how group (San To, or Komun Do) which forms Port Hamilton(Tonaikai), Dagelet Island(Utsuryo To, or Matsu Shima), Liancourt Rocks(Takeshima), and all other islands and islets to which Japan had acquired title lying outside … and to the east of the meridian 124°15′E. longitude, north of the parallel 33°N. latitude, and west of a line from the seaward terminus of the boundary approximately three nautical miles from the mouth of the Tumen River to a point in 37°30′N. latitude, 132°40′E. longitude….”

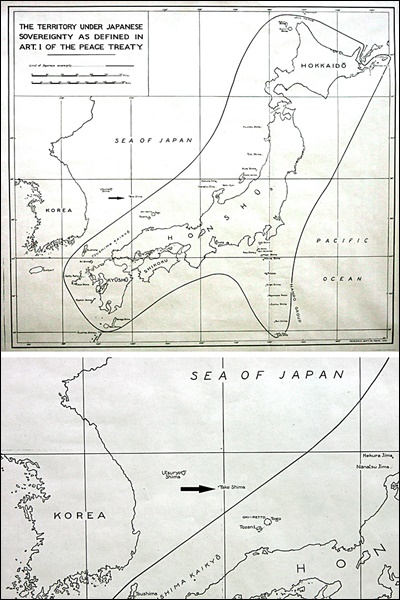

“…This line is indicated on the map attached to the present Agreement…”

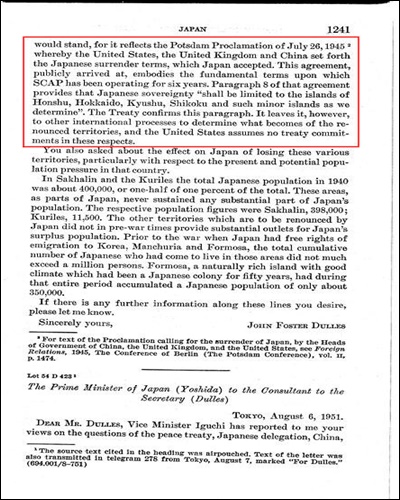

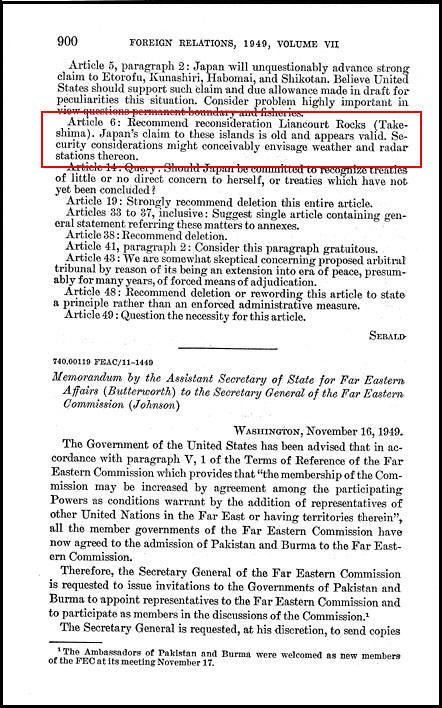

Drafts three, four and five, the same regarding Liancourt Rocks, all clearly had Japan renounce Dokdo Takeshima in favour of Korea. The attached image is Article 6 from the fifth draft of the Japan Peace Treaty. To the right is a copy from the fifth draft of the American Proposal for the Japan Peace Treaty issued on November 2nd 1949. Here we can read;

Drafts three, four and five, the same regarding Liancourt Rocks, all clearly had Japan renounce Dokdo Takeshima in favour of Korea. The attached image is Article 6 from the fifth draft of the Japan Peace Treaty. To the right is a copy from the fifth draft of the American Proposal for the Japan Peace Treaty issued on November 2nd 1949. Here we can read;

“…Japan hereby renounces in favor of the Korean people all rights and titles to Korea (Chosen) and all offshore Korean islands, including Quelpart (Saishu To); the Nan How group (San To, or Komun Do) which forms Port Hamilton (Tonakai); Dagelet Island (Utsuryo To, or MatsuShima); Liancourt Rocks (Takeshima); and all other islands and islets to which Japan had acquired title lying outside the line described in Article 1 and to the east of the meridian 124˚15˙E. longitude, north of the parallel 33˙N. latitude, and west of a line from the seaward terminus of the boundary at the mouth of the Tumen River to a point in 37˚30˙N. latitude, 132˚40˙E. longitude. This line is indicated on Map No. 1 attached to the present Treaty…”

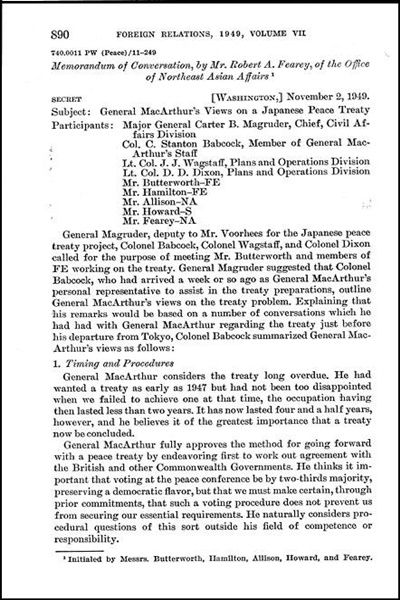

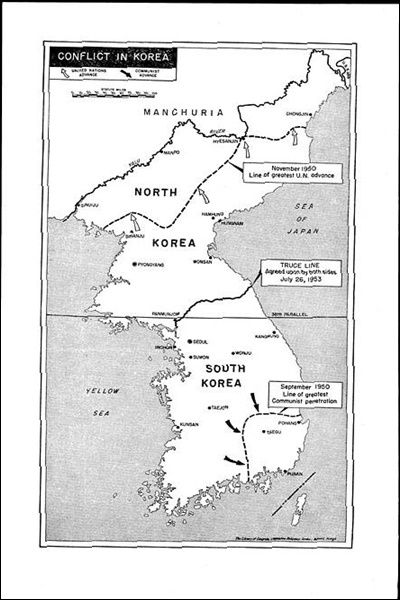

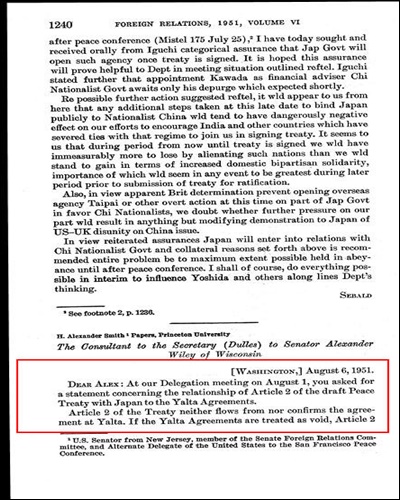

As the earlier Japan Peace Treaty Draft above shows the Americans decided that Liacourt Rocks should be transferred to the Koreans in at least five drafts of the Japan Peace Treaty. So what exactly transpired immediately after the fifth November 2nd draft that would have William Sebald make a complete shift in policy only two weeks later? U.S. Foreign Relations documents also on November 2 1949 detailing a conversation with General MacArthur stating his views regarding the Japan Peace Treaty may hold the clue.

Here it was recorded:

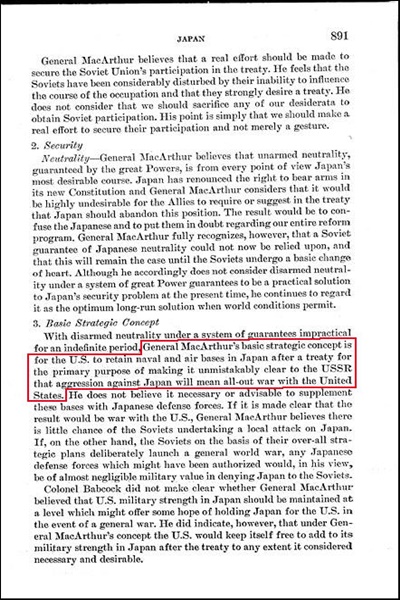

“…General MacArthur’s basic strategic concept is for the U.S. to retain naval and air bases in Japan after a treaty for the primary purpose of making it unmistakably clear to the USSR that aggression against Japan will mean all-out war with the United States…”

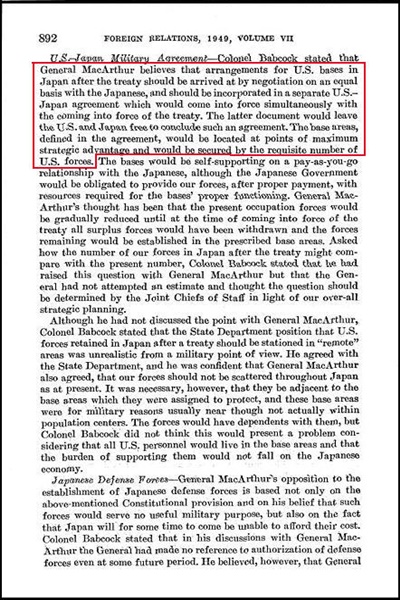

“…General MacArthur believes that arrangements for U.S. bases in Japan after the treaty should be arrived at by negotiation with Japan on an equal basis with the Japanese, and should be incorporated into a separate U.S. Japan agreement which would come into force simultaneously with the coming into force of the treaty. The latter document would leave the U.S. and Japan free to conclude such an agreement. The base areas defined in the agreement, would be located at points of maximum strategic advantage and would be secured by the requisite number of U.S. forces…”

America’s support for Korean sovereignty over Dokdo Takeshima continued until the Japanese intensified their lobbying campaign toward the Americans, General MacArthur’s military policy also was a huge factor.

America’s support for Korean sovereignty over Dokdo Takeshima continued until the Japanese intensified their lobbying campaign toward the Americans, General MacArthur’s military policy also was a huge factor.

As Shimane Prefecture’s Brochure points out, on November 14th 1949, Political Advisor in Japan William Sebald stated, “…Japan’s claim to this island is old and appears valid…” However, Shimane’s Brochure left out the next line. It states “…Security considerations might conceivably envisage weather and radar stations thereon…” Notice first Sebald states “reconsider” meaning they had already decided Dokdo Takeshima was Korean territory. It’s not clear how the U.S. came to the conclusion Dokdo Takeshima belonged to Japan as Korea was not given a chance to raise a contrary claim at this point but we know military considerations were a high priority.

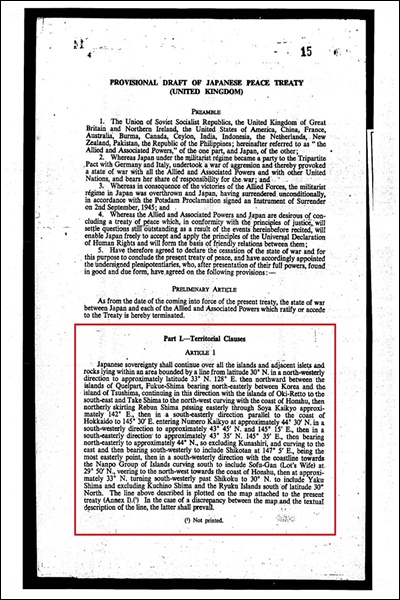

In the sixth draft of the Japan Peace Treaty we can see Takeshima was included as part of Japan. This draft reads as follows:

“…CHAPTER II

TERRITORIAL CLAUSES

Article 3

1. the territory of Japan shall comprise the four principal Japanese islands of Honshu, Kyushu, Shikoku and Hokkaide and all adjacent minor islands, including the islands of the Inland Sea(Seto Naikai) ; Tsushima, Takeshima(Liancourt Rocks), Oki Retto, Sado, Okujiri, Rebun, Riishiri and all other islands in the Japan Sea(Nippon Kai) within a line connecting the farther shores of Tsushima, Takeshima and Rebun…cont…”

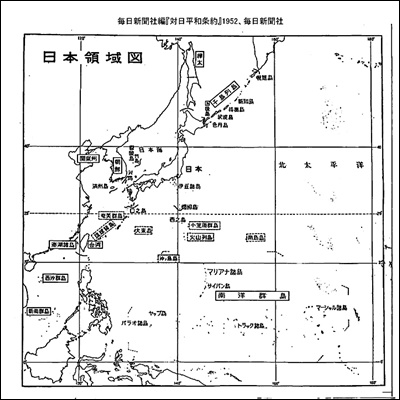

As shown above, the U.S. desired to install a military weather and radar station on Dokdo Takeshima. This could be accomplished through joint security trusteeships between Japan and the U.S. if incorporated into the Japan Peace Agreement. Eventually the Americans would acquire sign joint trustee agreements on some of the outlying islands through the the San Francisco Peace Treaty such as Marcus Island. As a result still, the U.S. still has bases on some of these islands today (ie Okinawa).

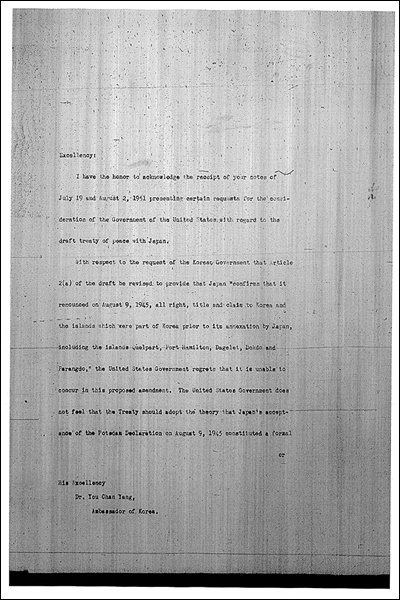

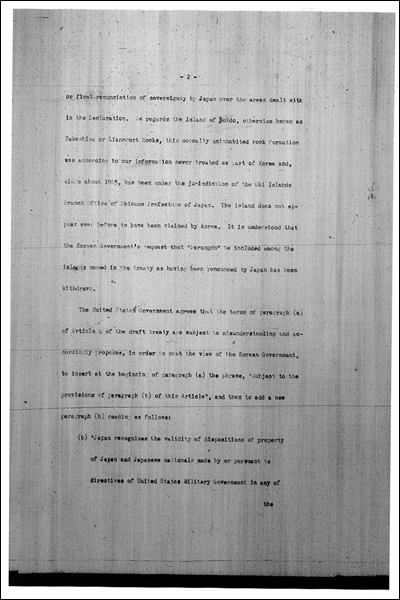

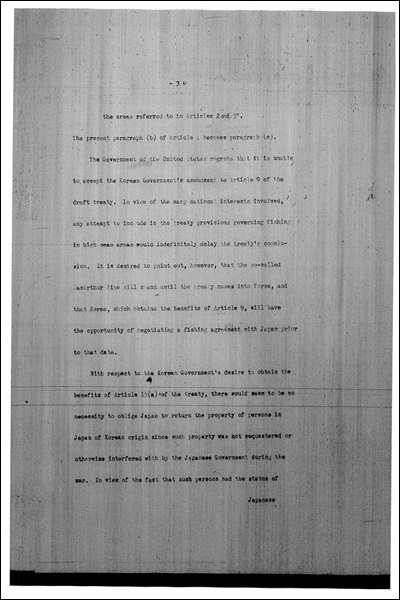

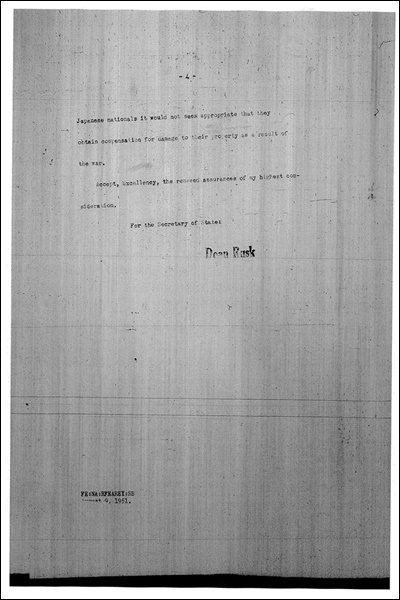

In an August 9, 1951 letter to the Korean Ambassador, US Secretary of State Dean Rusk wrote the following:

“…As regards the island of Dokdo, otherwise known as Takeshima or Liancourt Rocks, this normally uninhabited rock formation was according to our information never treated as part of Korea and, since about 1905, has been under the jurisdiction of the Oki Islands Branch of Shimane Prefecture of Japan. The island does not appear ever before to have been claimed by Korea….”

Dean Rusk was involved in military affairs throughout his life and political career. In World War II he joined the infantry as a reserve captain (he had been a ROTC Cadet Lieutenant Colonel), Rusk served in Burma as a staff officer and ended the war as a colonel with the Legion of Merit and Oak Leaf Cluster.

Dean Rusk was involved in military affairs throughout his life and political career. In World War II he joined the infantry as a reserve captain (he had been a ROTC Cadet Lieutenant Colonel), Rusk served in Burma as a staff officer and ended the war as a colonel with the Legion of Merit and Oak Leaf Cluster.

Dean Rusk returned to America to work briefly for the War Department in Washington. He was made Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs in 1950 and played an influential part in the US decision to become involved in the Korean War.

As Secretary of State, Dean Rusk was consistently hawkish, a believer in the use of military action to combat Communism. During the Cuban missile crisis he initially supported an immediate military strike, but he soon turned towards diplomatic efforts. His public defense of US actions in the Vietnam War made him a frequent target of anti-war protests.

In this exchange it can be read Dean Rusk supported Japan’s claim to Dokdo Takeshima. However, as we continue to study more American records from the Japan Peace Treaty archives we will see these papers do little more than show U.S. decisions on territorial ownership were based largely on military strategy.

It should also be noted, The Rusk Papers were confidential memorandums. None of Rusk’s opinions were made public nor conveyed to the Japanese government. In fact, they weren’t made public until decades later. Thus, the Rusk papers never materialized in official U.S. support for Japan’s claim to Dokdo. Rusk’s views were just one phase of America’s policy toward Dokdo that would later change into a neutral stance on the issue.

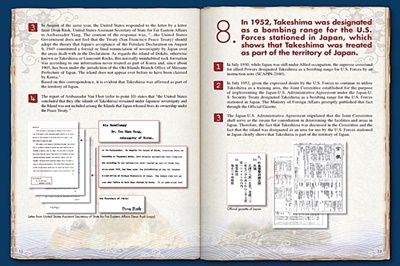

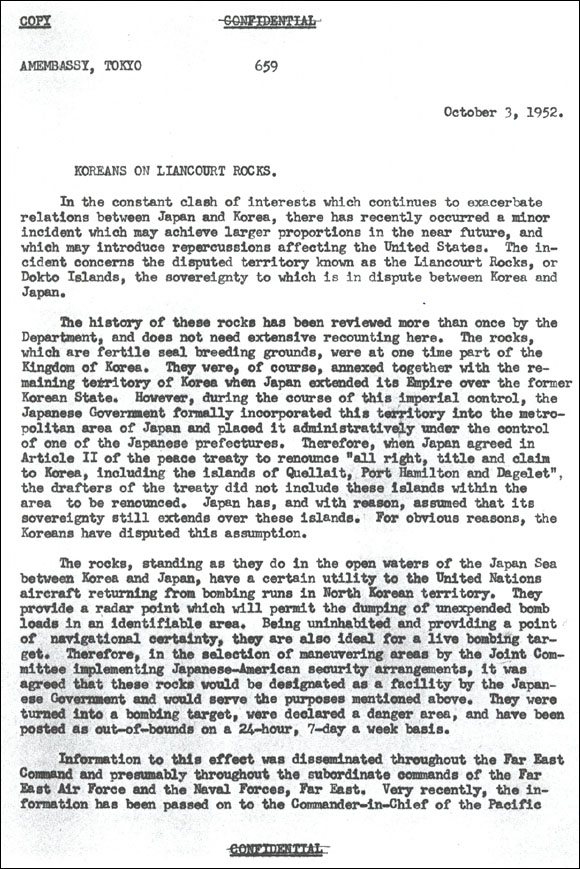

“…The history of these rocks has been reviewed more than once by the Department, and does not need extensive recounting here. The rocks, which are fertile seal breeding grounds, were at one time part of the Kingdom of Korea.They were, of course, annexed together with the remaining territory of Korea when Japan extended its Empire over the former Korean State…”

“…The rocks standing as they do in the open waters of the Japan Sea between Korea and Japan have a certain utility to the United Nations aircraft returning from bombing runs in North Korean territory. They provide a radar point which will permit the dumping of unexpended bomb loads in an identifiable area. Therefore in the selection of maneuvering areas by the Joint Committee implementing Japan America security arrangements, it was agreed these rocks would be designated a facility by the Japanese Government and would serve the purposes mentioned above…”

In this case it seems the needs of the Americans and Allied Command took precedent over the belief Liancourt was Chosun land. It also shows why Dokdo was designated as a facility of the Japanese government earlier. Thus, although some considered Dokdo Takeshima Korean territory the needs of the U.S. Military came first.

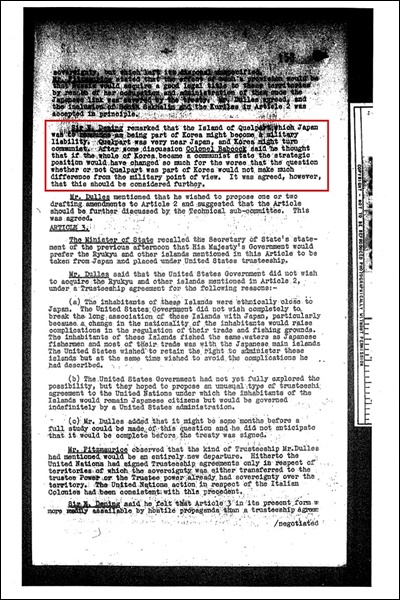

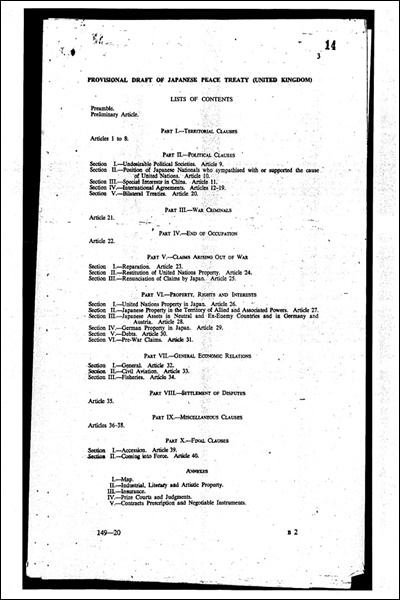

The British also considered this idea, as this documents reveals. It reads:

“…Sir Dening remarked that the island of Quelpart (Chejudo) which Japan was to renounce as being part of Korea, might become a military liability. Quelpart was very near Japan might turn communist. After some discussion Colonel Babcock said he thought that if the whole of Korea became a communist state the strategic position would have changed so much more for the worse that the question of whether or not Quelpart (Chejudo) was part of Korea would not make much difference from the military point of view. It was agreed, however, that this would be considered further…”

Thus, we know from these records true historical title was not the grounds for allied decisions in the disposition of land.

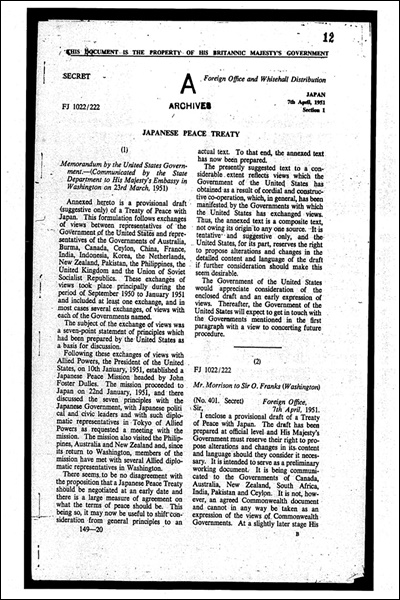

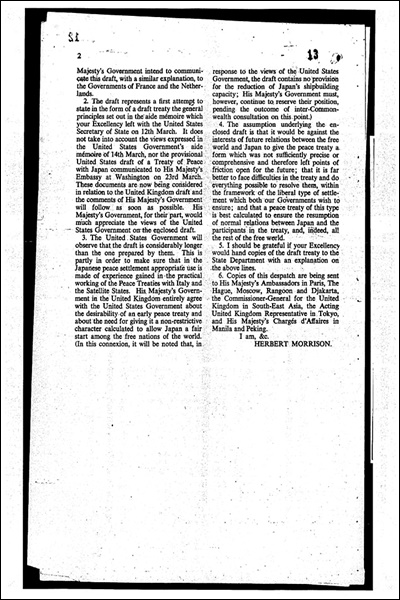

This became apparent in a Top Secret Foreign Affairs document from January 1951 intended for Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. The confidential letter was issued after Dean Rusk, and Allison had a meeting with the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

It stated:

It stated:

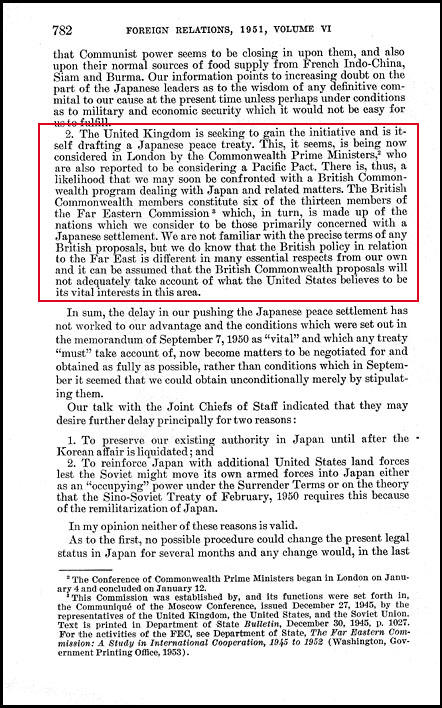

“…The United Kingdom is seeking to gain the initiative and is itself drafting a peace treaty… We are not familiar with the precise terms of any British proposals, but we do not know that the British policy in relation to the Far East is different in many essential aspects from our own and it can be assumed that the British Commonwealth proposals will not adequately take account of what the United States believes to be its vital interests in this area…”

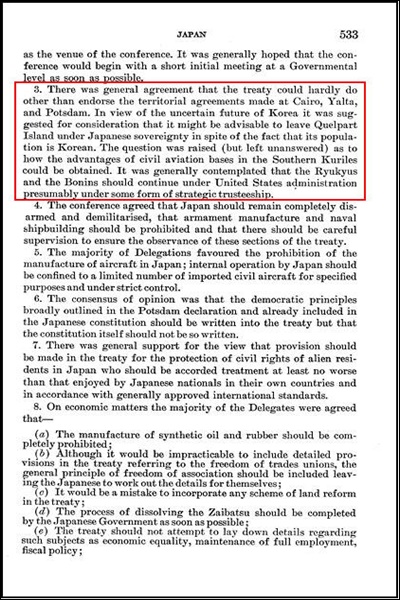

As we see, the views of other countries regarding Dokdo Takeshima diverged from U.S. Foreign Policy. For example, the United Kingdom’s requested a linear boundary in the East Sea (Sea of Japan) that would have placed Dokdo Takeshima within Korean territory. The Americans objected saying the Japanese “felt psychologically boxed in” by this proposal.

Also, we can read there was a growing sense of urgency for the Americans to quickly implement the Japan Peace Treaty and Joint Trusteeships of former Japanese territories. The disagreements between other Allied Forces may have been the reason. It may also explain why some issues remained resolved (Dokdo, Sahkalin etc.) even after the San Franciso Peace Treaty was signed.

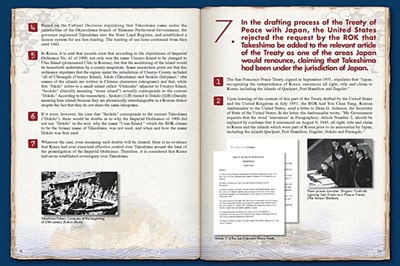

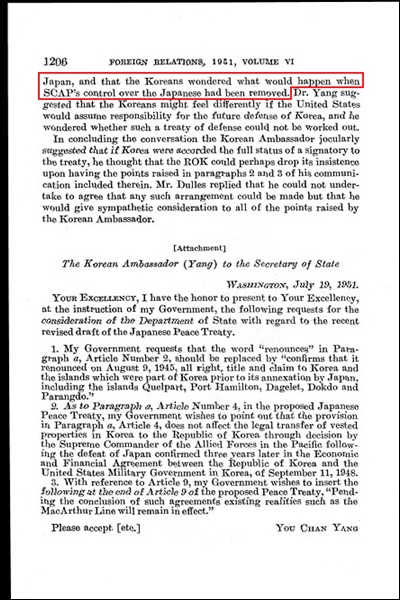

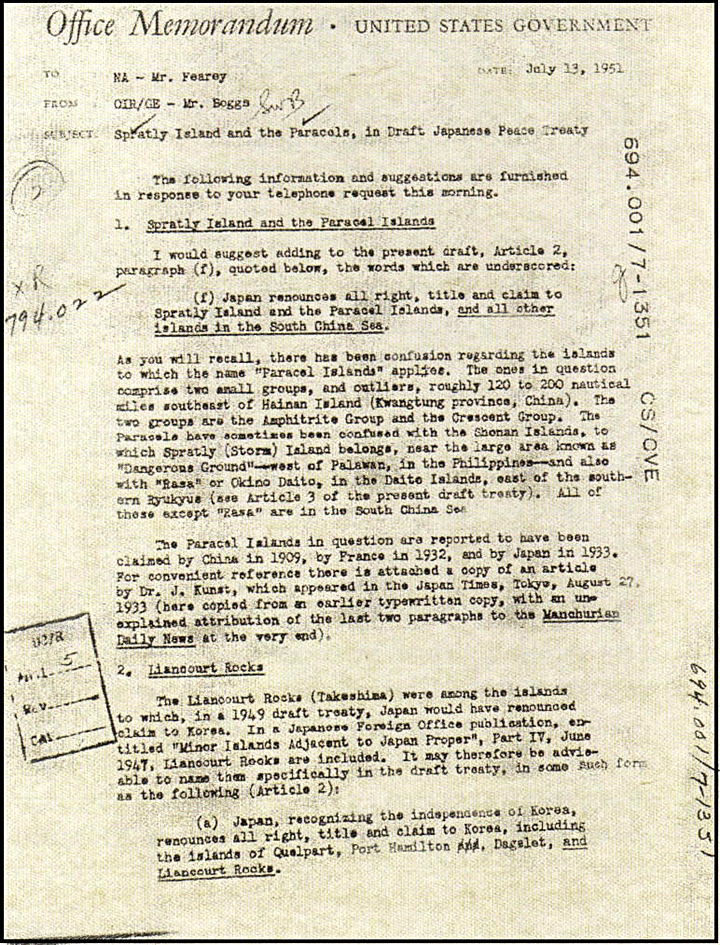

Even some Americans were not enthusiastic about ceding Dokdo Takeshima to Japan. On July, 13th 1951 A State Department Geographer at the Office of Intelligence and Research, S.W. Boggs, replied to a inquiry from Robert A. Fearey about territories that might be in contention between Japan and other countries after the signing of the peace treaty. In regards to the islands in the East Sea/Sea of Japan, Boggs suggests that:

“…Liancourt Rocks”(Dokdo) could be included in the peace treaty, and that it might be “advisable to name the territories specifically in the draft treaty, in some such form as the following (Article 2): (a) Japan, recognizing the independence of Korea, renounces all right, title and claim to Korea, including the islands of Quelpart, Port Hamilton, Dagelet, and Liancourt Rocks…”

“…Liancourt Rocks”(Dokdo) could be included in the peace treaty, and that it might be “advisable to name the territories specifically in the draft treaty, in some such form as the following (Article 2): (a) Japan, recognizing the independence of Korea, renounces all right, title and claim to Korea, including the islands of Quelpart, Port Hamilton, Dagelet, and Liancourt Rocks…”

Boggs’ reply is special. Being a State Department Geographer his rationale behind defining Japan’s territory represents a practical approach to the dispute not tainted by military ambitions but rather on the geopolitical reality of the region. His memorandum foreshadows the potential for conflict the Dokdo Takeshima dispute had even decades ago. S.W. Boggs’ solution remains a logical answer to the problem even today. He knew declaring the border of Japan~Korea between Ulleungdo and Dokdo would have been a huge mistake. In the end, the modern border between Japan and Korea is right where Bogg’s suggested and to this day we have a fair boundary considering the region’s geography.

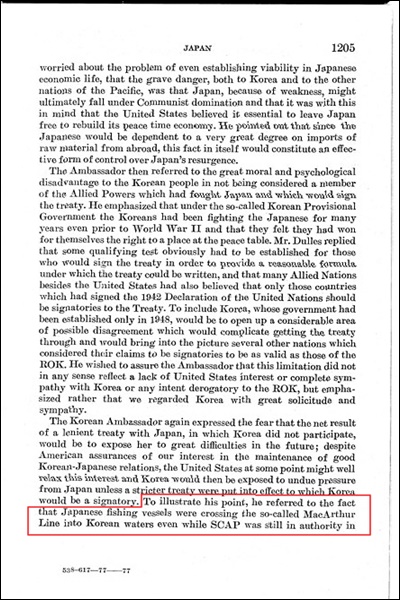

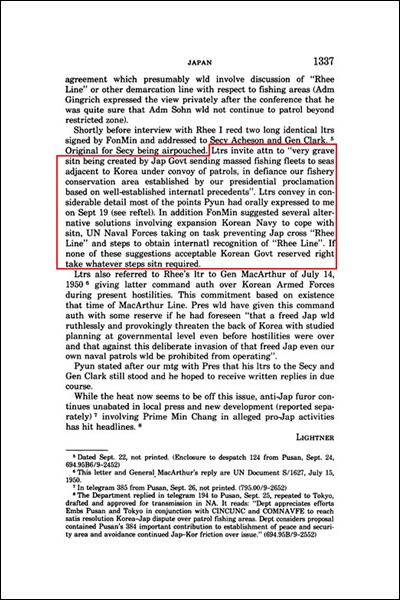

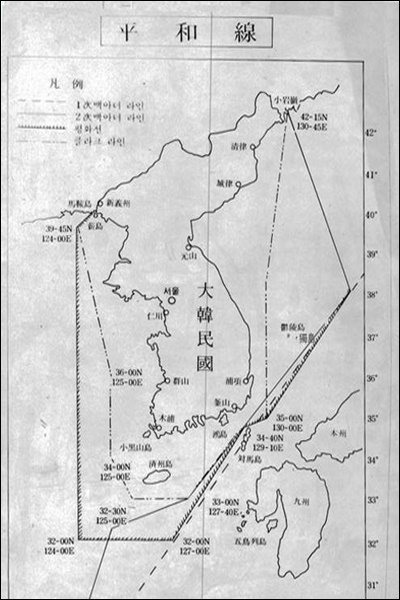

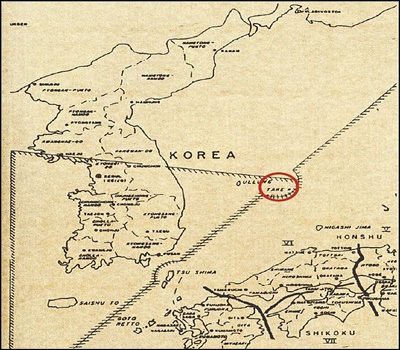

Korea’s President was deeply concerned Allied Command was not enforcing the MacArthur Line and felt the Americans were much too lenient at the expense of the ROK. President Rhee was also worried about what would happen when Japan was no longer under the restrictions of Allied Command’s SCAPIN orders. Indeed, if Japan didn’t respect powerful Allied Command it’s unlikely they would comply with Korean demands to stay within fishing limits.

What becomes immediately apparent is Syngman Rhee’s “Peace Line” is almost identical to the numerous Allied maps that already proposed a boundary between Japan and Korea. They too had logically concluded the limit of Japan’s waters should be slightly East of Dokdo Takeshima

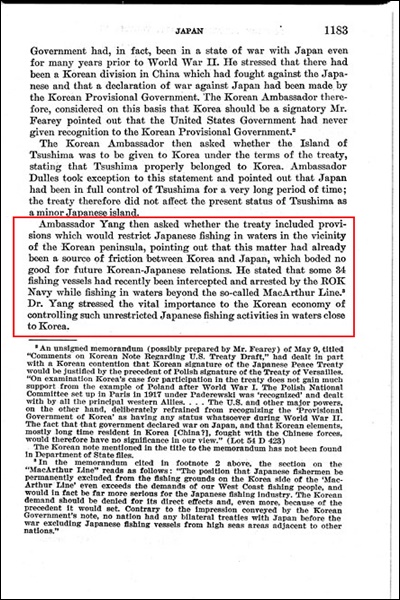

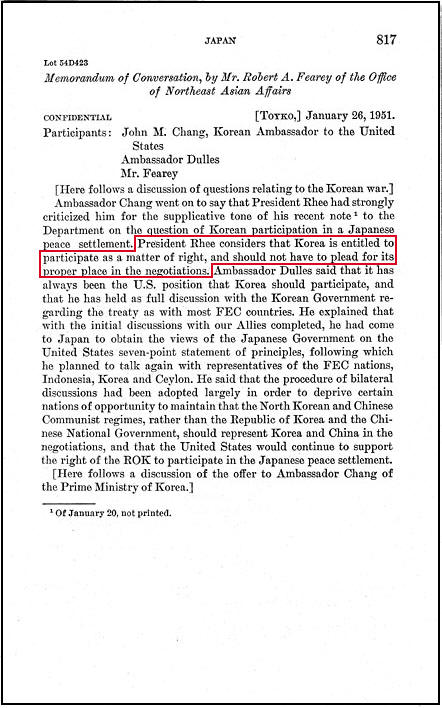

During the Japan Peace Treaty negotiations Syngman Rhee expressed his frustration that the ROK wasn‘t permitted to directly participate in discussions that would ultimately define South Korea’s national boundaries. Korea was not allowed to sign the Japan Peace Treaty. On January 26, 1951 the Koreans conveyed their dissatisfaction with being frozen out of the talks while Japan and the U.S. had conducted bilateral negotiations.

Here it could be read:

“…President Rhee considers that Korea is entitled to participate as a matter of right, and should not have to plead for its proper place in the negotiations…” (see left image)

When the South Koreans came to the realization they were not being fairly represented, President Rhee took matters into his own hands. He simply solidified the Japan Korea boundary already implemented by the previous directives from Allied Command such as SCAPIN 677, SCAPIN 1033 (aka MacArthur Line) and previous WWII Agreements such as the Cairo Convention and the Potsdam Declaration.

In the end there was no mention of Liancourt Rocks in the San Francisco Peace Treaty. The allied powers did not indicate why they chose to remain silent on the outcome, but the varying positions taken during the deliberation process indicate that the decision was made either because not enough information had bee provided regarding the historical events surrounding Japan’s incorporation of Dokdo Takeshima or because the Allied Powers felt themselves incapable or inadequate adjudicators. To this day, America maintains a neutral stance on the Dokdo Takeshima dispute.

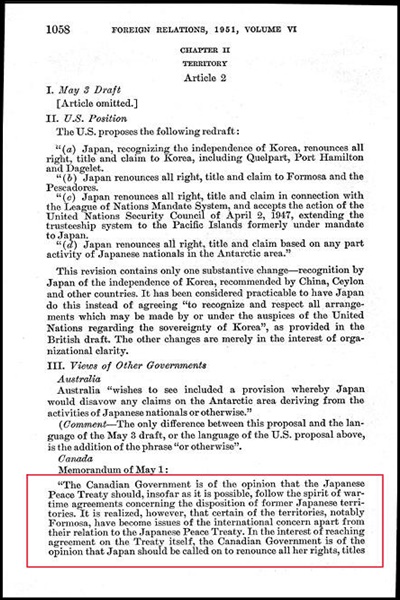

CHAPTER II

TERRITORY

“..Article 2

(a) Japan recognizing the independence of Korea, renounces all right, title and claim to Korea, including the islands of Quelpart, Port Hamilton and Dagelet.

(b) Japan renounces all right, title and claim to Formosa and the Pescadores.

(c) Japan renounces all right, title and claim to the Kurile Islands, and to that portion of Sakhalin and the islands adjacent to it over which Japan acquired sovereignty as a consequence of the Treaty of Portsmouth of 5 September 1905.

(d) Japan renounces all right, title and claim in connection with the League of Nations Mandate System, and accepts the action of the United Nations Security Council of 2 April 1947, extending the trusteeship system to the Pacific Islands formerly under mandate to Japan.

(e) Japan renounces all claim to any right or title to or interest in connection with any part of the Antarctic area, whether deriving from the activities of Japanese nationals or otherwise.

(f) Japan renounces all right, title and claim to the Spratly Islands and to the Paracel Islands…”

The Allies Formally Exclude Dokdo From Japan’s Territory

What is the truth about Dokdo Takeshima and the Japan Peace Treaty? What was the status of Japanese territory at the conclusion of the San Francisco Peace Treaty?

At the San Francisco Peace Conference, on September 5th, 1951, three days before the signing of the Japan Peace Treaty, former Senator John Foster Dulles delivered his famous speech that clarified both Articles 2 and 3 of the Japan Peace Treaty. In Dulles’ speech not only is America’s true political stance on Japan’s territory conveyed, the legal effects and limits of Potsdam, Scapin 677 and the new Japan Peace Treaty are laid down.

“…What is the territory of Japanese sovereignty? Chapter II deals with that. Japan formally ratifies the territorial provisions of the Potsdam Surrender Terms, provisions which, so far as Japan is concerned, were actually carried into effect 6 years ago.”…The Potsdam Surrender Terms constitute the only definition of peace terms to which, and by which, Japan and the Allied Powers as a whole are bound. There have been some private understandings between some Allied Governments; but by these Japan was not bound, nor were other Allies bound. Therefore, the treaty embodies article 8 of the Surrender Terms which provided that Japanese sovereignty should be limited to Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, Shikoku and some minor islands. The renunciations contained in article 2 of chapter II strictly and scrupulously conform to that surrender term.

Some question has been raised as to whether the geographical name “Kurile Islands” mentioned in article 2 includes the Habomai Islands. It is the view of the United States that it does not. If, however, there were a dispute about this, it could be referred to the International Court of Justice under article 22.

Some Allied Powers suggested that article 2 should not merely delimit Japanese sovereignty according to Potsdam, but specify precisely the ultimate disposition of each of the ex-Japanese territories. This, admittedly, would have been neater. But it would have raised questions as to which there are now no agreed answers. We had either to give Japan peace on the Potsdam Surrender Terms or deny peace to Japan while the Allies quarrel about what shall be done with what Japan is prepared, and required, to give up. Clearly, the wise course was to proceed now, so far as Japan is concerned, leaving the future to resolve doubts by invoking international solvents other than this treaty.

Article 3 deals with the Ryukyus and other islands to the south and southeast of Japan. These, since the surrender, have been under the sole administration of the United States.Several of the Allied Powers urged that the treaty should require Japan to renounce its sovereignty over these islands in favor of United States sovereignty. Others suggested that these islands should be restored completely to Japan.

In the face of this division of Allied opinion, the United States felt that the best formula would be to permit Japan to retain residual sovereignty, while making it possible for these islands to he brought into the United Nations trusteeship system, with the United States as administering authority…”

John Foster Dulles’ public statements were representative of official U.S. policy. Not only did Dulles help draft the Japan Peace Treaty, he was signatory. So although the U.S. supported Japan secretly regarding Takeshima, John Foster Dulles made it clear. With regard to territory, the Potsdam Declaration, Scapin 677, and its formally modified version (Japan Peace Treaty) were the only signed agreements that had the legal clout to bind both Japan and the Allies.

Dulles Reiterates U.S. Position Regarding Liancourt Rocks

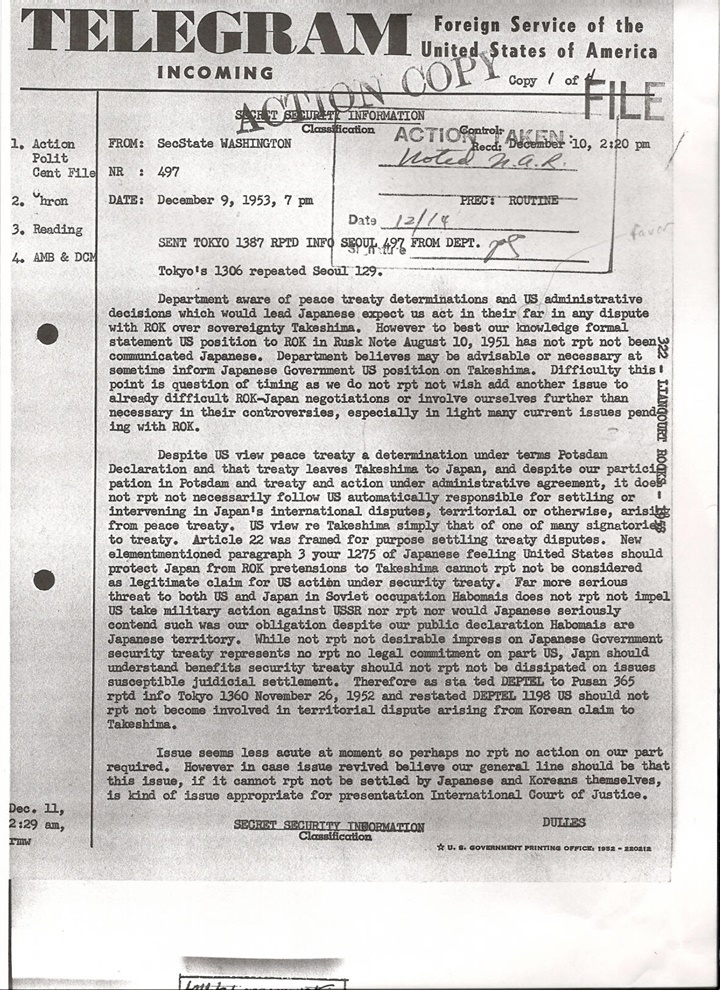

America Pulls the Plug on Japan, December 9th, 1953

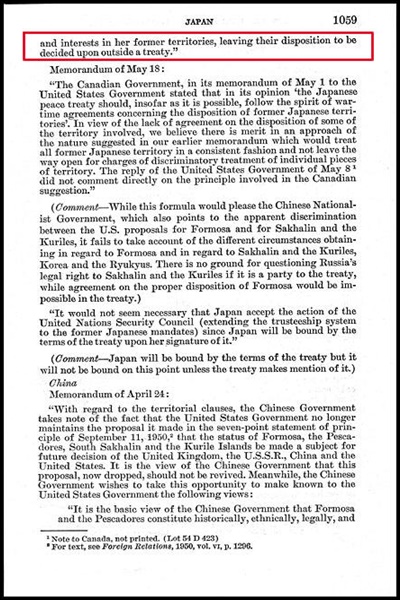

This document also shows us America’s support for Japan was based on her interpretations regarding the relevance of the Postdam Declaration and the Cairo Convention not international law. In sharp contrast, other nations such as Canada and Russia took these WWII Treaties literally and desired to resolve Japan’s territorial disputes outside of the framework of the Japan Peace Treaty. It’s no coincidence the U.S. dropped support for Japan shortly after the armistice was signed ending the Korean War on July 27th 1953. With U.S.-ROK relations improving the American’s could now maintain a footprint on the Asian mainland and ownership of Liancourt Rocks became a non-issue.

Japanese lobbyists insist America’s omission of Liancourt Rocks amounts to her regaining sovereignty over the island. The comments made by Dulles disproves this. He states if Japan has a problem with the definition of Japan’s territory she should take it up with the ICJ as stated in Article 22 of the Japan Peace Treaty.

Japanese lobbyists insist America’s omission of Liancourt Rocks amounts to her regaining sovereignty over the island. The comments made by Dulles disproves this. He states if Japan has a problem with the definition of Japan’s territory she should take it up with the ICJ as stated in Article 22 of the Japan Peace Treaty.

Most importantly the U.S. washes her hands clean of the Dokdo Takeshima issue by stating “The U.S. view is one of many signatories of the treaty…” In other words, even if America did support Japan Dulles insists America’s opinion carries no more weight than that of the other 47 nations who signed the Japan Peace Treaty. Thus, Dulles admits America could not unilaterally make any judgements regarding the disposition of former Japanese territories without the consent of all signatory nations to the treaty.

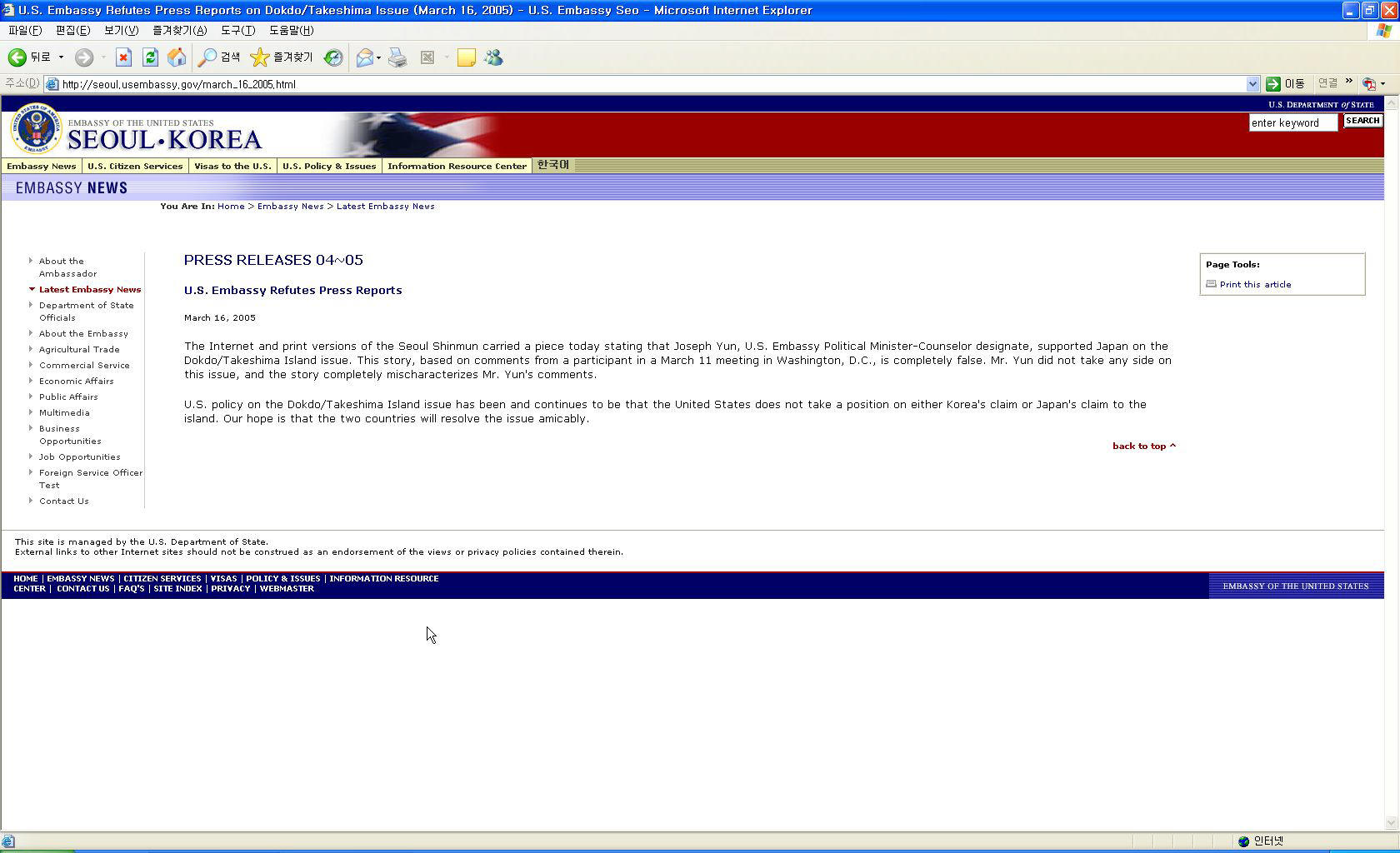

To put an end to any assertions America supported or supports Japan’s claim to Takeshima a 2005 public statement by the American Embassy is Seoul sets the record straight. It states “…U.S. policy on the Dokdo/Takeshima issue has been and continues to be that the United States does not take a position on either Korea’s claim or Japan’s claim to the island…”

Most importantly the U.S. washes her hands clean of the Dokdo Takeshima issue by stating “The U.S. view is one of many signatories of the treaty…” In other words, even if America did support Japan Dulles insists America’s opinion carries no more weight than that of the other 47 nations who signed the Japan Peace Treaty. Thus, Dulles admits America could not unilaterally make any judgements regarding the disposition of former Japanese territories without the consent of all signatory nations to the treaty.

To put an end to any assertions America supported or supports Japan’s claim to Takeshima a 2005 public statement by the American Embassy is Seoul sets the record straight. It states “…U.S. policy on the Dokdo/Takeshima issue has been and continues to be that the United States does not take a position on either Korea’s claim or Japan’s claim to the island…”

As both Japan’s MOFA and Shimane Prefecture Brochure’s above show us, the Japanese assert Allied Command determined that Dokdo Takeshima belonged to Japan. They have come to this conclusion based on some confidential U.S. Government memorandums that were exchanged at the time of the Japan Peace Treaty negotiations. Japan’s assumption these papers amount to ownership of Dokdo Takeshima is wrong on a few points.

First, the most obvious error by the Japanese is The San Francisco Peace Treaty simply makes no mention of Dokdo Takeshima. The Allies simply couldn’t arrive at an agreement and dropped the matter. This shows other countries couldn’t agree with U.S. policy on this problem. Other nations (U.K. N.Z. Canada) that participated in the talks had a different approach to establishing Japan’s limits. They wanted to follow the spirit of post wartime documents such as the Cairo Convention and the Potsdam Declaration and leave the contentious issue of outlying islands to be resolved outside of the treaty altogether. Commonwealth nations proposed a linear boundary between the Okinoshimas and Dokdo Takeshima. This was much more practical approach but it didn’t work for America’s military plan in northeast Asia.

Sadly to say, the Koreans were not allowed to directly participate in these talks even though the Koreans voiced their objections. In hindsight it’s quite outrageous Korea was not permitted to become involved in the negotiating process that would define the territorial boundaries of her own country. As a result, Korea was not allowed to sign the San Francisco Peace Treaty. Therefore, at least it shows this treaty has no legal effect on the Republic of Korea. Similarly when the USSR declined to sign the treaty, the U.S. Government conceded the San Francisco Peace Treaty had no binding legal effect on the Russians.

The Japanese government wishes to demonize former President Rhee’s for his harshly imposed “Peace Line” but when we compare this limit from other borders agreed upon by Allied Command, the Rhee’s Peace Line in almost identical. Obviously the ROK became frustrated watching the Allies divide up the region and decided to take matters into her own hands. Simply put, after centuries of Japanese invasions into Korea’s coastal waters and islands the ROK initiated, and enforced, a border defence policy based on the only principle the Japanese would respect. Brute force.