Ulleungdo Governor, Bae Gye Ju (Pei Kei Chu ) accompanied E. Laporte during this inspection. Bae Gye Ju was among Ulleungdo’s first settlers during Chosun’s new immigration policy toward Ulleungdo, arriving in 1881. He was from Gangwan Province and became a full time resident of Ulleungdo. He was said to be quite amicable and spoke fluent Japanese. Bae Gye Ju was also somewhat of an entrepreneur who hoped to profit from Ulleungdo’s abundant timber.

Ulleungdo Governor, Bae Gye Ju (Pei Kei Chu ) accompanied E. Laporte during this inspection. Bae Gye Ju was among Ulleungdo’s first settlers during Chosun’s new immigration policy toward Ulleungdo, arriving in 1881. He was from Gangwan Province and became a full time resident of Ulleungdo. He was said to be quite amicable and spoke fluent Japanese. Bae Gye Ju was also somewhat of an entrepreneur who hoped to profit from Ulleungdo’s abundant timber.Bye Gye Ju lived at Dodong Harbor amongst Ulleungdo’s largest concentration of Japanese residents. In 1895 he was appointed as Governor of Ulleungdo, and became Governor Of Uldo County in 1900. The lawless behavior of Japanese on Ulleungdo would prompt Bae Gye Ju to levy new taxes on any economic activities on Ulleungdo in 1902. The following records explain why Chosun (Korea) began to implement new laws on Ulleungdo.

My Lord,

Seoul, July 24th 1899.

The Local Governor of Dagelet, (Ulleungdo) an island which lies off the East coast of Corea, in latitude 37-30 North, and longitude of 131 East, having recently complained of to Seoul of the harsh treatment which the natives were receiving at the hands of Japanese settlers, Mr. McLeavy Brown the Chief Commissioner of Customs was requested by the Central Government to send the Commissioner of Customs at Fusan (Busan) to inquire into the circumstances on the spot.

Mr Brown has courteously furnished me, confidentially, with the Report received from the Commissioner, and as it contains some interesting details respecting an almost unknown island, and illustrates the manner in which outlying portions of this country are being exploited by the Japanese, I venture to transmit a copy of it herewith to your Lordship.

I have, &c

(signed) J.N. Jordan

(Confidential)

Sir,

Custom House, Fusan, July 6, 1899

In accordance with the instructions contained in the letter of the 22nd of June, I have the honour to report that, in company with Mr. Pei Kei Chu (Bae Gye Ju), the Government official of Woo Lung Do (Ulleungdo), and Mssrs, Kim Long Won and Araki of the Busan Office I preceeded in the Corean LS “Hyenik” on a visit to Dagelet Island.

Leaving Busan at 4 P.M. in the afternoon of the 28th, the highest peak of Dagelet Island was sighted for the first time at 7 AM the next morning, though it was not until 1 PM in the afternoon of the 29th that we arrived close on shore.

The appearance of Woo Lung Do, as the steamer approaches it from the South , is very beautiful, and striking is the contrast afforded by its green and wooded collines when compared with the barren hills of the mainland.

The area of the island was roughly estimated by Captain Benzenius at 25 square miles, and the whole of its superficies, with the exception of a few patches of cultivated land, is covered from the shores, rising in most cases abruptly from the sea, to the summit of its highest mountain, 4,000 feet high, by a thick growth of large trees of all kinds.

Within a mile from the shores the chart shows a depth of water ranging from 1,000 to 1,600 fathoms, and in several instances the lead, thrown almost at the foot of the towering cliffs, gave no bottom at 100 fathoms; the water is, in consequence, so blue and clear that for experiments sake, a bottle, lowered over the side with a line, could be distinctly seen at a depth of 25 feet.

Native Population

The present population is said to be 3,000 adults and children, living in some 500 hundred houses, not grouped together, but scattered all over the hills and along the shore, according to the exigencies of the owner’s trade, and nowhere have I seen more than thirty houses together.

In 1879 Dagelet (Ulleungdo) was a desert(ed) island. It is during that year that the first settlers crossed over from the mainland. Kang Wan Do, distant about 70 miles. The pioneers appear to have been boat-builders, desirous of utilizing for their trade the wealth of timber growing on the island; then followed farmers, merchants, and fishermen. The latter, however, are not large in numbers, as the fish is not plentiful, and the great depth of the water proves a considerable impediment to the divers seeking sea-weed and shell-fish; still over 2,000 piculs of sea-weed are, I was told, exported yearly from the island.

The number of inhabitants is continually increasing; this is due to the facts that life on the island is comparatively easy, that there are few or no taxes, and that the soil is so rich that no manure is ever needed or used. The settler, on landing, goes in search of a piece of land as flat and easy of access as the island affords: having found it, he sets fire to the brush-wood and trees to clear away his ground. When the fire has burnt itself out, he builds a house from the material close at hand, removes as far as possible the roots of the charred trees and scratches slightly the surface of the soil which is then ready to receive seeds and to yield two crops every year, wheat or barley in the spring, potatoes or beans in the autumn. Deliciously cool water is found in abundance, brooks running everywhere from the hillsides, but I remarked with surprise the total absence of all the domestic animals that form so familiar a sight in a Corean village; during my walks on shore I did not see a dog, a pig, a horse or a cow, and even chickens seemed very scarce.

Native Industries, Trade, Produce &c.

Boat-building is the only industry on the island; orders for the construction of boats are received in the spring from Kang Wang Do, Kyong San Do, Chulla Do and Quelpart (Cheju Island), and the new junks are generally completed and ready to sail in November, before the heavy weather sets in. Trade with the mainland is insignificant…(continued)

Occasionally a junk arrives with immigrants; she carries in addition to men and their humble belongings a few bags of rice, native tobacco and some piece goods; when the cargo is sold and the money realized she sails back loaded in most cases with sea-weed, sometimes with planks. There is little demand for heavy timber on the mainland, but were there a ready market, very little trade could still be done on it, as the Corean junks would prove and unsurmountable obstacle. Owing to the steepness of the ground, rice cannot be grown on Dagelet and the Coreans live mostly on wheat, barley and potatoes. The crops raised last year consisted of 20,000 bags of potatoes, 20,000 bags of barley, 10,000 bags of yellow beans, and 5,000 bags of wheat. A thick forest of pine trees of great age and size covers every hill of the island, while various species of valuable hard woos are also found in abundance amongst others: Kiyak wood, a kind of sandal wood, a tree called by the Coreans ‘Pak-Cha’ and one called ‘Kam-tan’ the bark of which is used by the Japanese for manufacturing bird-lime.

The Japanese on Dagelet, their Smuggling and Wood-Cutting.

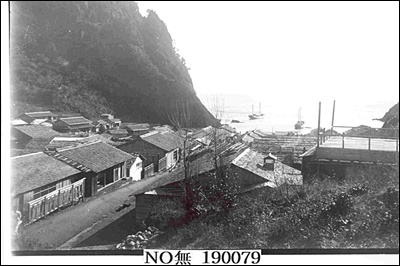

Under Mr. Pei’s advice, the steamer first proceeded to the eastern side of the island where, I was told, the largest Japanese Settlement was situated. After passing ‘Seal Point’ almost concealed in the middle of the cliffs, we found a small bay, the entrance to which, about 100 feet wide, could be easily overlooked by vessels passing some distance off the coast. There in a gully was build a village of 40 odd houses, of huts, the residence of 140 Japanese men and 23 women. On the beach 5 Japanese junks and 2 schooners empty, were, were hauled up out of reach from the heavy swell; one small Japanese junk was afloat, loaded with 280 bags of beans; she left two hours after our arrival and we were told that two large schooners, with valuable cargoes of timber, had gone to Japan on the 27th of June. The crews of the seven vessels, sixty men about, brought the Japanese population on that spot alone to over 200.

Enormous logs of hard wood, already cut and sawn ready for shipment were lying everywhere, while every house contained articles of importation amongst which the most important were rice, salt, porcelain, saki, grey shirtings, cotton wadding, kerosene oil, matches and umbrellas. Three junks the Yebisu, Koyei and Sluoyei Maru, produced permits to ship from the Saki Customs (Itoki Province) clearly showing that these junks had brought full import cargoes and had cleared in Japan for Busan.

The import goods are seldom sold to the Coreans for ready money, but in most cases exchanged against beans, barley, or seaweed, the value of the articles of exportation being fixed by the Japanese as follows..

1 koku of beans (about 5-13 bushels , or 293 lbs.) .. .. 2 00 = 4 0

1 koku of barley (about 5-13 bushels , or 267 lbs.) .. .. 2 00 = 4 0

1 koku of wheat (about 5-13 bushels , or 307 lbs.) .. .. 165 = 3 3

1 picul of potatoes (133 lbs) .. .. 0 30 = 0 7

1 picul of seaweed (133 lbs) .. .. 2 00 = 4 7

Or somewhat under half of what the same goods would cost if purchased at Busan.

Two Japanese, Wakida Shotaro and Amano Genzo, appear to be the Headmen of the wood-cutting concern, working with the official’s permission (I am giving you father the Corean version of the case, and how this permission came to be granted) employing workmen and being the principal exporters to Japan; but I imagine that all the Japanese on the island help themselves more or less freely to the richness placed undefended within their reach. To kill the trees they remove the bark, allowing them to stand until they become “seasoned”, after six months or so the trees are cut down, sawn, and ready for sale. The majority of the Japanese came from the Oki Islands distant about 160 miles, and arrived at Dagelet (Ulleungdo) in 1894, though a few claim to have lived on Dagelet seven or eight years.

On the northern side I visited two Japanese settlements, one occupied by twenty-five Japanese and the other by fifteen Japanese men and one woman; ten Japanese fishing boats and one Japanese junk were in course of construction, and a blacksmith’s shop was in full operation. In both places I found the same evidences of illicit trade carried on with Japan. The sixteen inhabitants of this last village had, at the sight of the ‘Hyenik,’ taken to the hills, and it is only with the greatest of difficulty that I….(continued)

managed to prevent the Coreans from setting fire to the Japanese houses and from hunting the owners up the mountains.

This leads me to mention the numerous complaints preferred by Coreans of the rough treatment they receive at the hands of the Japanese throughout the island, complaints embodied in a Petition handed to me by the Headment of several villages, and which I have the honour to enclose.

Amongst minor grievances, the Coreans lay great stress on a somewhat serious affray that took place in April of this year. Some Japanese having assaulted a native (Corean) women, the Coreans collected together to demand some kind of satisfaction, but the Japanese turned out in force, armed with guns and swords, and a discharge, which wounded one man, sent the Coreans running back to their villages. To pacify the victors the official in charge of the island during Mr. Pei’s absence was compelled to give them a written permission to cut a few trees. I was unable to obtain, either from the Corean official of the Japanese a copy of this permission.

Taxes, &c.

Farmers and merchants pay no taxes. The official collects 10 per cent of all the seaweed obtained from the sea and brought on the island, and a tax on the wood employed for boat-building, and averaging 10,000 cash for each junk built.

With the exception of a commission of two per cent to the brokers or middlemen who assist them in disposing of their goods, the Japanese pay no taxes. No doubt some years ago the official did try and probably succeeded in obtaining from the Japanese some compensation for the timber carried away, but having seen their present strength and their attitude (there are in 250 residents without counting the crews of vessels), I am convinced that they pay neither tax nor squeeze of any kind and that officials and people alike have only one wish, to get rid as soon as possible of the unwanted visitors.

Another settlement with about thirty Japanese, mostly employed in sawing wood, is situated on the south coast of Dagelet, but though I attempted it, I was presented from landing there by the heavy surge running on that side.

We left again at 5 P.M. on the 30th reaching Busan, without incident, at 4 P.M. on the 1st July.

Separately I am sending a sample of Kiyaki wood, of sandal wood, and samples of beans, wheat, and barley.

I am, &c.

(signed) E. LAPORTE.

We also get an understanding of why Chosun decided to declare Ordinance 41 in October of 1900. Bae was obviously trying to re-establish that Ulleungdo, Jukdo Islet and Dokdo were indisputably Korean territory. Bae would further attempt to control the Japanese by declaring new tax laws in 1902 affecting Ulleungdo’s exports of sea products and timber.