Why is it so important to explain the situation in 1905?

Can we move back the Republic of Korea’s modern territorial limit to the colonial era?

The civilian invasion of Korea’s Ulleungdo’s Island was the whole foundation for Japan’s involvement on Liancourt Rocks and later illegal incorporation of the island. Japanese squatters and poachers conducted their activities on Liancourt Rocks via Chosun’s Ulleungdo. In both Korean and Japanese historical records these Japanese trespassers were described as ignorant, violent an very aggressive. Japan’s Foreign Affairs Official himself stated the squatters resorted to brute force and were potential murderers. Through time, Chosun Administrators became afraid to govern over Ulleungdo Island.

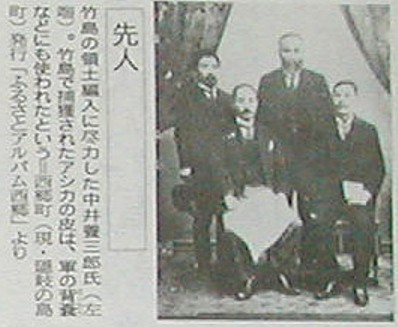

One of these trespassers would be utilized by the Japanese government for what Japanese assert was a “legal” basis for their current claim to Dokdo Takeshima.

One of these trespassers would be utilized by the Japanese government for what Japanese assert was a “legal” basis for their current claim to Dokdo Takeshima.

Nakai Yozaburo, (shown right) a Japanese squatter on Korea’s Ulleungdo filed for an application to lease the island claiming he was living on Liancourt Rocks and was occupying the islets. In reality his operation was conducted from Chosun’s Ulleungdo and the civilian incorporation was merely a “legal” cover (link) for Japan’s real ambitions to construct naval watchtowers on Liancourt Rocks (link)

Below we will see how Japan’s Foreign Minister Hayashi Gonsuke refused to remove these aggressive trespassers and then stationed Japanese police on Ulleungdo without the consent of the Korean government.

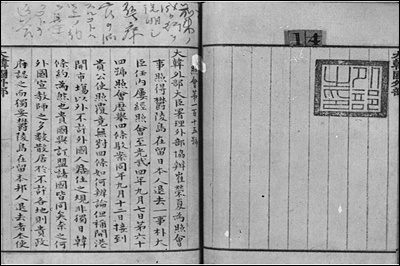

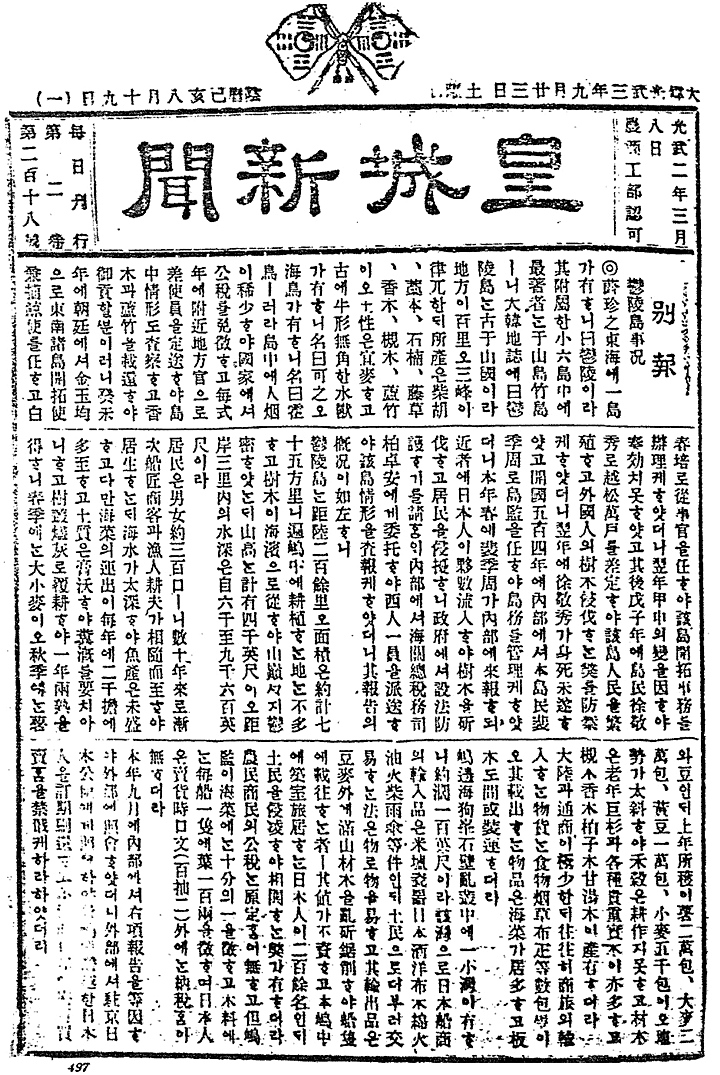

“…In 1895 (開國五百四年에), the Ministry of the Interior appointed island resident Bae Gye-ju as the Island Supervisor and had him manage the island. In the spring of this year (1899), Bae Gye-ju reported to the Ministry of Interior that Japanese had recently been arriving in large numbers and were cutting down trees, encroaching on residents, and causing disturbances and requested that the government establish law and order.

“…In 1895 (開國五百四年에), the Ministry of the Interior appointed island resident Bae Gye-ju as the Island Supervisor and had him manage the island. In the spring of this year (1899), Bae Gye-ju reported to the Ministry of Interior that Japanese had recently been arriving in large numbers and were cutting down trees, encroaching on residents, and causing disturbances and requested that the government establish law and order.

This prompted the Interior Ministry to request Sir John McLeavy Brown, chief commissioner of the Korean Customs Service, to dispatch one Westerner to the island to investigate the situation there. The exported goods include wood that is cut indiscriminately from all over the mountain, loaded onto ships, and carried away, the price is insufficient.

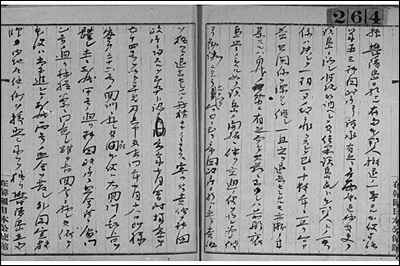

There are places on the island where about 200 Japanese have built houses and are living temporarily (squatting). They encroach on the locals and have inappropriate relations. When the Japanese sell goods, they pay only a negotiated fee of two percent, but no tax. In September of this year, the Interior Ministry, based on the above report, requested that the Foreign Ministry request the head of the Japanese mission in Korea to promise to set a date to remove the Japanese trespassing on the island and stop and prohibit the smuggling trade from non-trade ports…” (click picture for larger image)

“..Illegal Japanese Tree Felling? Grant Japan logging rights…!”

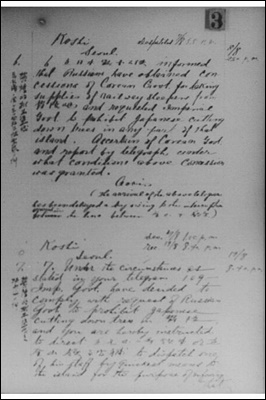

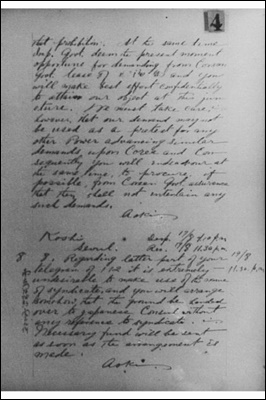

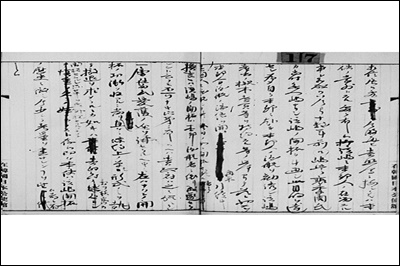

Under the circumstances as stated in your telegram 109 Imperial Govt. have decided to comply with request of Russian Govt. to prohibit Japanese cutting down trees in 鬱陵島 and you are hereby instructed to direct 在元山二等領事 or 在釜山領事官補 to dispatch one of his staff by quickest means to the island for the purpose of informing that problem. At the same time Imperial Govt. deem the present moment opportunity for demanding from Corean Govt. lease of 巨濟島 and you will make best effort confidentially to obtain our object at this juncture. We must take care, however, that our demand may not be used as a protest for any other power advancing similar demands upon Corea and consequently you will endeavor at the same time, to procure if possible, from Corean Govt. assurance that they shall not entertain any such demands.

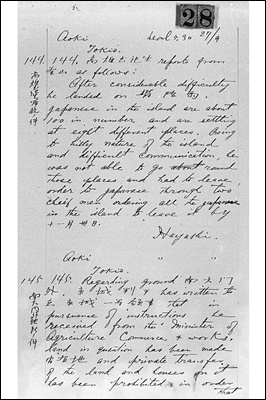

Aoki, Tokio144. 高雄書記官 reports from 釜山 as follows:

After considerable difficulty he landed on 鬱陵島. Japanese on the island are about 100 in number and are settling at eight different places. Owing to hilly nature of the island and difficult communication he was not able to go round these places and had to leave order to Japanese through two chief men ordering all the Japanese in the island to leave it by 十一月三十日.

Seoul, 18/10. 2:30 p.m. (1899-10-18)

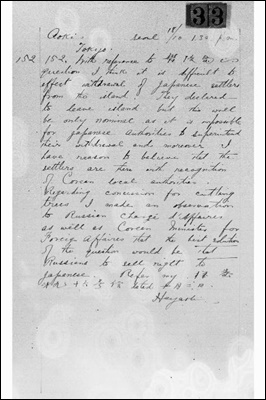

Aoki, Tokyo 152. With reference to 鬱陵島 question I think it is difficult to effect withdrawal of Japanese settlers from the island. They declared to leave island, but this will be only nominal as it is impossible for Japanese Authorities to superintend their withdrawal and moreover I have reason to believe that the settlers are there with recognition of Corean local authorities. Regarding concession for cutting trees I made an observation to Russian Charge d’Affaires as well as Corean Minister for Foreign Affairs that the best solution of the question would be that Russians to sell right to Japanese. Refer my 機密第九十六號信 dated 九月□日…”

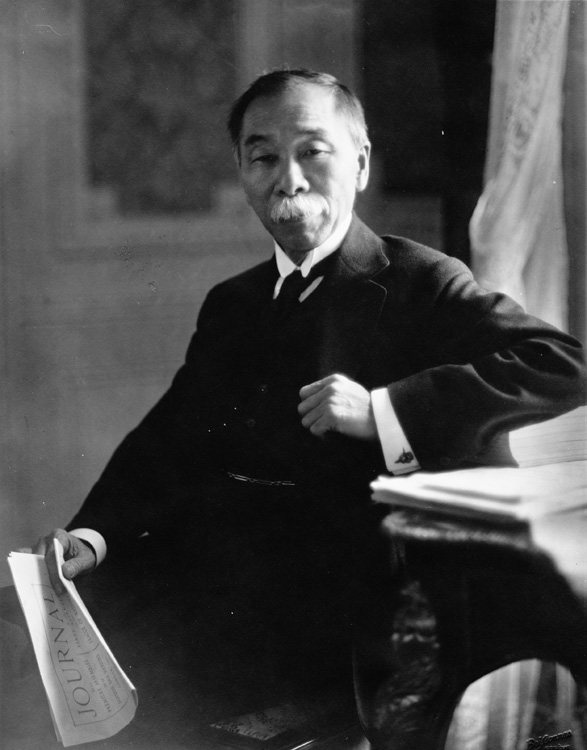

Hayashi (shown to the right) also played an important role in opening up Korea for Japanese settlers by lobbying for Japanese land ownership. Hayashi Gonsuke was instrumental in the pushing forth of legislation for Japanese citizens to buy and settle on Korean territory.

Hayashi (shown to the right) also played an important role in opening up Korea for Japanese settlers by lobbying for Japanese land ownership. Hayashi Gonsuke was instrumental in the pushing forth of legislation for Japanese citizens to buy and settle on Korean territory.

He was a supporter of the Nagomori Plan presented by Nagamori Fujiyoshiro. Nagamori’s plan was intended to allow Japanese private citizens to circumvent treaty restrictions that banned land ownership outside of settlement zones. Hayashi Gonsuke also negotiated a secret agreement with Foreign Minister Yi Ha-Yong allowing Japanese nationals to make mortgage loans to Koreans secured by users rights on their lands. These mortgage deals had stipulations transferring ownership on the land if the Korean defaulted on the loan.

As the record above shows, Japan’s Foreign Affairs Minister Hayashi was informed of the desperate situation on Korea’s Ulleungdo Island.

Well before the Russo~Japanese War (1904~1905) the clandestine purchase of land by Japanese was well under way. Local authorities would often turn a blind eye to these transactions, formally requesting the Japanese to get off of the land, but doing nothing if they refused. This could have been the case on Korea’s Ulleungdo Island.

Hayshi’s political background explains why he refused to have illegal squatters on Ulleungdo removed. First, Hayashi was heavily in favour of the Japanese annexation over all of Korea. Also it is understood he was a strong supporter of Japanese ownership of land and immigration in Korea. By turning a blind eye to the Japanese trespassers on Ulleungdo he could effortlessly accomplish both aims.

By Hayashi’s own admission the Japanese on Ulleungdo were ignorant, tough and even potential murderers. He describes their use of brute force to resolve disputes. Also contained in this letter are references from previous Koreans who had the unenviable task of trying to administer over now chaotic Ulleungdo. It seems the Chosun governors on Ulleungdo now feared the worst and were afraid to govern over their own island. Hayashi gave Korea one option, allow the deployment of Japanese police either temporarily or permanently. What’s more shocking however, is his own admission this was not in compliance with Japan-Korea treaty regulations. As we will see even though Hayashi knew the stationing of Japanese Police was illegal, in the end he would refuse to remove them.

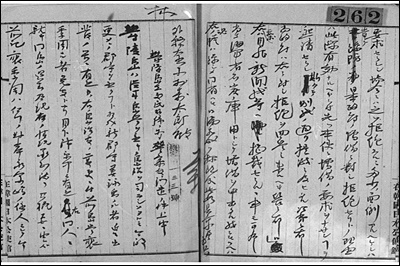

“…So now the Korean population on Ulleungdo is between 5,000-6,000 and the Japanese inhabitants number between 300-400, It has even peaked at 1,000 Japanese people. The rise and fall of Japanese people on Ulleungdo is only related to the fishing season. Among those Japanese mentioned above about 30-40 of them have already built dwellings and are living as settlers. Many of these Japanese settlers are ignorant and tough. However, since there are no authorities controlling them (Japanese), any disputes between residents are resolved only through brute force and in worst cases even murder. Especially with Koreans they resorted to the use of physical force, therefore the island’s administrator had difficulty controlling the island…”

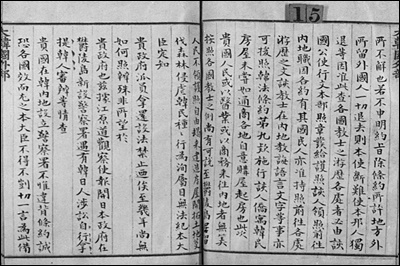

“…The matter of removing those Japanese living on Ulleungdo has been requested several times by the Korean government since this office has been established. Therefore, we sent our officials there twice to investigate the situation and they concluded that the relationship between Korean Ulleungdo residents and our Japanese citizens has developed over the last decades and has grown even stronger these days. For this reason, even if they (Japanese) are removed it’s only natural to assume that more and more people will return (to Ulleungdo). To discuss how things have reached this point, as Administrator Bae cited, it was those (Koreans) who requested to seek transportation convenience through the development of the island who are responsible. Therefore, at this point, the Imperial Government of Japan has no obligation to remove these Japanese from Ulleungdo Island. Rather, we have concluded it’s only fair to deem this problem a responsibility of the Korean government….”

“…The matter of removing those Japanese living on Ulleungdo has been requested several times by the Korean government since this office has been established. Therefore, we sent our officials there twice to investigate the situation and they concluded that the relationship between Korean Ulleungdo residents and our Japanese citizens has developed over the last decades and has grown even stronger these days. For this reason, even if they (Japanese) are removed it’s only natural to assume that more and more people will return (to Ulleungdo). To discuss how things have reached this point, as Administrator Bae cited, it was those (Koreans) who requested to seek transportation convenience through the development of the island who are responsible. Therefore, at this point, the Imperial Government of Japan has no obligation to remove these Japanese from Ulleungdo Island. Rather, we have concluded it’s only fair to deem this problem a responsibility of the Korean government….”

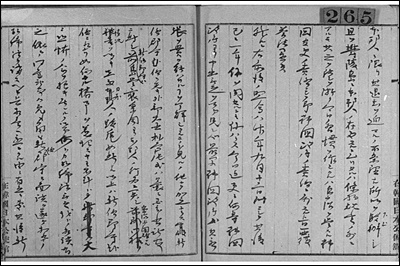

“…Last year, in confidential memorandum #54 of July 4th, a detailed report was written of my personal views on this matter. That year on July 18th our (Japan’s) government replied with official instructions of confidential memorandum #36. With these instructions in mind, this (Japan’s) office immediately asked the Korean government via attached letter A and received a (Korea’s) reply of letter B saying that Chosun’s government can’t agree with our recommendations. As as result this office sent attached letter C and explained why it is absurd to prompt us to remove Japanese residents particularly from Ulleungdo, while foreign missionaries are allowed to live in Korea. It is also stated (by Japan) that the act of our Japanese people’s living on Ulleungdo is excluded from treaty regulations. We also replied that it is the Korean authorities of Ulleungdo who are to blame for the problems that have developed there and thus the Korean government should be held responsible…” (cont)

“…Thus, in light of Baek Gye Ju’s recorded dialogue, and also in order to ascertain the intentions of your (Korean) government if we implement laws for our Japanese people on the island (Ulleungdo) we believe we can watch and control their behavior. We then could achieve mutual harmony between the island’s (Ulleungdo’s) residents (Japanese and Koreans) and there won’t be any need to remove them. These laws seem to work best if we incorporate this island (Ulleungdo) into the Japanese Empire’s consulate police district in Pusan or Wonsan. We could then dispatch a police administrator along with perhaps two police officers on Ulleungdo every six months or year having fixed alternating deployment periods. This is comparable to the system we have in Gaesoeng which is under the jurisdiction of our consulate’s police district in Seoul. Since there are 50~60 Japanese residents, we have a police station there and dispatch officers to stay watching our people’s behaviour. We acknowledge under treaty law, this is not a given right Japan can impose upon your government but in reality the Korean government has tacitly consented on this and has never raised an objection. Therefore, if this Ulleungdo matter can be considered as the same and our Japanese police can be stationed there, as justification for watching our people’s behavior, the problems on Ulleungdo will naturally be resolved. Accordingly, this will prevent trouble, like having to forcibly remove our (Japanese) I’ve written the circumstances so far asking for your opinion, hoping you would consider what the minister said earlier and use your position for support…”

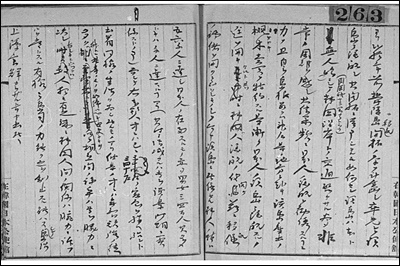

Instead your (Japanese) letter only stated “…The regulation that foreign residents are prohibited from living outside of open ports or cities does not only apply to Japanese and Korean agreements, it also applies to other friendly nations of yours. However why does your (Korean) government demand our Japanese to leave Ulleungdo while the Korean government allows other foreign missionaries to roam freely? Our (Japanese) diplomatic office can’t understand. Unless the Korean government removes all foreign residents from outside of the treaty designated open areas, our Japanese office can hardly consider removing Japanese nationals from your Ulleungdo Island…” (continued)

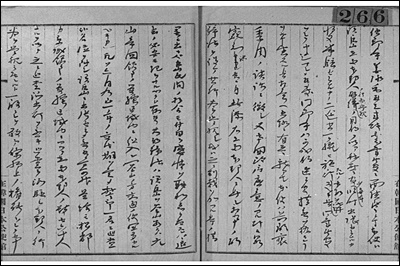

“…In response to your aforementioned statements, As to the foreign missionaries who travel around our country (Korea) Every one of the numerous countries made sure they submitted official documents before we issued them travel passes in accordance with the specific laws. These foreign nationals travel around the country with the travel passes issued by our (Korean) government. This is possible because there is an article in our treaties stating “foreigners of these countries are permitted to travel with this particular visa…” Also foreign missionaries of these particular countries are teaching languages etc., in accordance with article number 9 of Korean law and treaties.

“…In response to your aforementioned statements, As to the foreign missionaries who travel around our country (Korea) Every one of the numerous countries made sure they submitted official documents before we issued them travel passes in accordance with the specific laws. These foreign nationals travel around the country with the travel passes issued by our (Korean) government. This is possible because there is an article in our treaties stating “foreigners of these countries are permitted to travel with this particular visa…” Also foreign missionaries of these particular countries are teaching languages etc., in accordance with article number 9 of Korean law and treaties.

The foreigners who reside temporarily in Korean houses cannot be compared to those (Japanese) who buy Korean homes for trade (illegally) around the country. Under these conditions the number of Japanese who come and go for the purpose of medical work or business affairs cannot be calculated. However, they could be justified when we consider other previous examples such as missionaries. But these Japanese who reside on Ulleungdo came in illegally without the correct visas. They are building houses, cultivating the land, logging indiscriminately, and encroaching upon our (Korean) citizens. All of these activities are by no means legal….” (continued)

I request your office to look into this matter, report in detail to your government, and withdraw your police (from Ulleungdo). I also request your office to urge the nearest consulate to call back your citizens and comply with the purpose of our treaty. Please be mindful of our friendly relations…”

In light the above, it is only right that your government look for measures to take care of these Japanese residents more. But instead, now that some gains are near, your government is demanding their (Japanese citizens) removal simply insisting on the terms of our treaty law. This only shows your government’s lack of consideration about the history of Ulluendo’s development. In other words, our office is asking you to take into account the historical background of the island’s development. The dispatching and stationing of our Japanese police on Ulleungdo resulted from when Bak Jae Sun during his tenure requested measures to control our (Japanese) people residing there around the time Gang Yeong U was about to begin administering on Ulleungdo. Today your government is accusing us of “treaty violation” and this is absurd. When your letter comes to the part where “…when there is a dispute between a Korean and a Japanese the police simply take the liberty of arresting the Korea and interrogating him…” we find it impossible to believe our policemen would do such a thing. I’m sure there must have been a mistake but to be sure we will have the police supervisor issue a warning and speak to this policeman. Therefore we’d also like your government to talk to the governor of the island and urge him to carefully enforce the general law and administration, and especially police affairs on Ulleungdo. With this report we look forward to hearing from your valued opinion…”

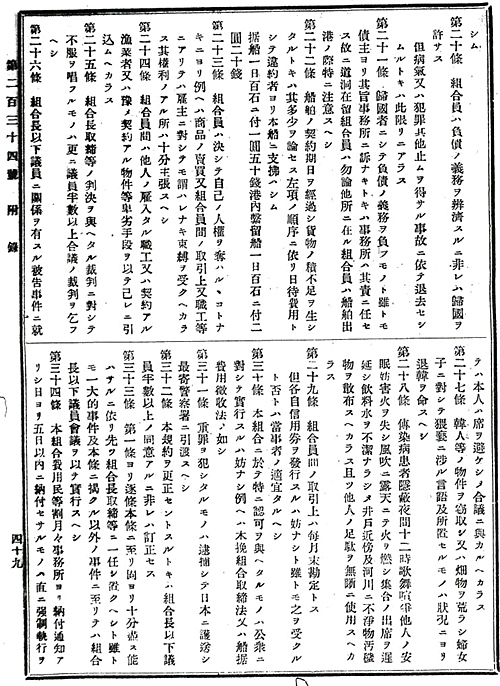

The General Situation of Japanese Residents:

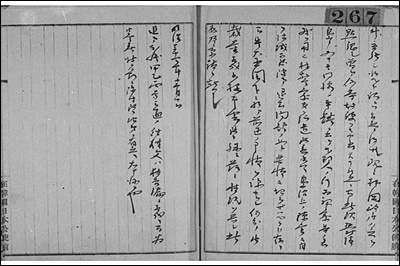

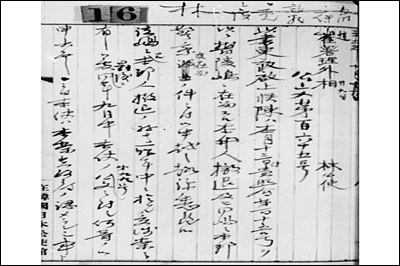

The General Situation of Japanese Residents:“…As more and more (Japanese) people came to live here, (Korea’s Ulleungdo) it was only natural that bad people also came, which created a need for regulation. This lead people to organize the so-called, Japanese Association of Commerce (日商組合?), which appointed two people to help protect the residents. However, as the population continued to grew rapidly, it became impossible to sort out the problems with that method of law enforcement. Moreover, since the most of the transients were ignorant and illiterate, two groups of people developed. The strong subjugated the weak, and the wise tricked the ignorant. Also, there was an extreme case, in which a bad person used a dangerous weapon to forcefully seize property.

The good people were deeply distressed by the bad people since there was no one to restrain them. Therefore, in July in the 24th year of Meiji (1902), important people in the community who were concerned with the situation held a meeting with the ordinary people, and they decided to reorganize the association. To eliminate the old, bad habits, they agreed to appoint a chairman and a vice-chairman, both without salary, and one paid superintendent…” (continued)

“…They also agreed to elect 15 honored assemblymen to work under them and deal with the problems and incidents that occurred through a process of council and judgement. The association tried hard to enforce the statutes. For example, they put criminals in a newly created detention center to try to get them to repent their crimes, and they sent people who had committed serious crimes back to the nearest police station in the homeland (Japan).

“…They also agreed to elect 15 honored assemblymen to work under them and deal with the problems and incidents that occurred through a process of council and judgement. The association tried hard to enforce the statutes. For example, they put criminals in a newly created detention center to try to get them to repent their crimes, and they sent people who had committed serious crimes back to the nearest police station in the homeland (Japan).

On January 4th of this year, a dispute erupted two groups. The former head of the association tried to disrupt the association, by convincing many of the lumbermen and other workers to leave the association and come over to his side. The present head tried everything he could to settle the dispute through arbitration, but he failed and ultimately accepted their leaving. Thus, all the Japanese residents on the island divided into two groups of people. More than three fourths of the residents left the association and only one-fourth remained.

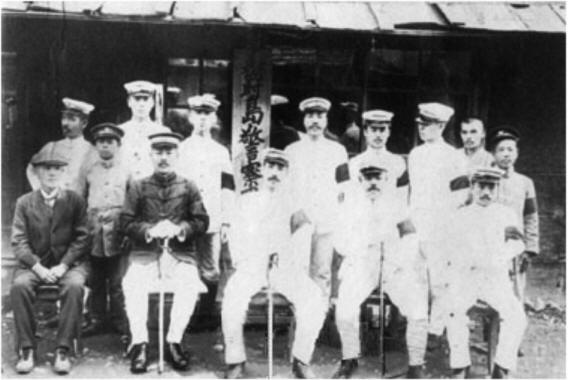

The two groups became hostile to each other not only in business dealings, but also in everyday dealings. Though the association shrank and was less prosperous, they continued to maintain order and never succumbed to the majority opposition. Then on April 23th of this year, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) decided to establish a police substation on the island…“

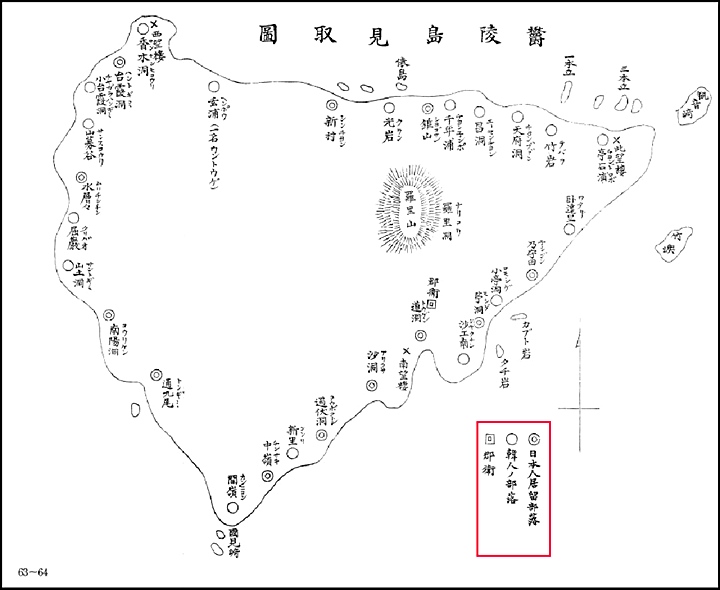

Dodong (道洞) – 27 Korean; 36 Japanese

Dodong (道洞) – 27 Korean; 36 JapaneseBokdong (伏洞) – 10 Korean; 2 Japanese

Jungryeong (中嶺) – 30 Korean; 2 Japanese

Tonggumi (通龜尾) – 20 Korean; 5 Japanese

Gul-am (窟巖) – 7 Korean

Sanmak-gok (山幕谷) – 26 Korean

Hyangmokdong (香木洞) – 17 Korean

Sinchon (新村) – 35 Korean; 1 Japanese

Chusan (錐山) – 7 Korean; 1 Japanese

Cheonnyeon-po (千年浦) – 6 Korean

Cheonbudong (天府洞) – 16 Korean

Jongseokdong (亭石洞) – 20 Korean

Naesujeon (乃守田) – 11 Korean; 2 Japanese

Sagongnam (砂工南) – 2 Korean

Sadong (沙洞) – 40 Korean; 2 Japanese

Sadong (沙洞) – 40 Korean; 2 JapaneseSinri (新里) – 7 Korean

Ganryeong (間嶺) – 10 Korean

Namyangdong (南陽洞) – 57 Korean; 9 Japanese

Sucheung (水層) – 1 Korean; 1 Japanese

Daehadong (臺霞洞) – 34 Korean; 6 Japanese

Hyeon-po (玄浦) – 50 Korean

Gwangam (光岩) – 10 Korean

Naridong (羅里洞) – 30 Korean

Changdong (昌洞) – 6 Korean; 2 Japanese

Jukam (竹岩) – 11 Korean; 5 Japanese

Wadalli (臥達里) – 2 Korean

Jeodong (苧洞) – 62 Korean; 5 Japanese

One Japanese report tells us the Japanese residents amounted to about 20% of the total population. However, in the spring, hundreds of Japanese fishermen would swarm Ulleungdo Island and their population would reach about one thousand. Today about ten thousand Koreans live on Ulleungdo Island and administer over Dokdo and Ulleungdo from the district office in Dodong on Ulleung Island.

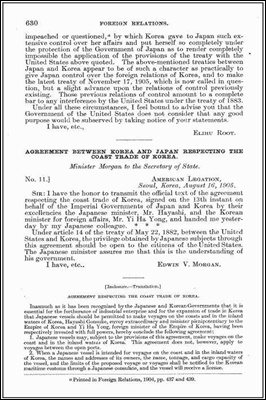

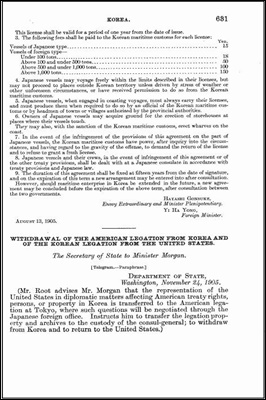

By 1902 Ulleungdo Island was controlled by Japanese police. In 1904, during the Russo Japanese War, Ulleungdo island was occupied by Japanese Naval Troops and three military watch towers and telegraph lines were installed. Only months after Japan annexed Dokdo 1905 the Japanese has secured access to Koreas coastal and inland waters. (see docs below) Of course, these days Ulleungdo Gun administers over both Ulleungdo Island and Dokdo. Unlike 1905 Japan does not have the right to fish and voyage in Korean waters.

Japan’s MOFA wishes to drag Korea back to the colonial era and contain the residents of Ulleungdo-Korea to a fraction of their current maritime limits. Japan aspires to extend Shimane Prefecture’s territory to the front doorstep of an island known as Korean land since the 6th Century. History teaches us that national boundaries are not static but fluid. Redrawing the maritime limits of Korea back to the colonial era is no different than trying to resurrect former Communist USSR. Korea and Japan can solve the Dokdo Takeshima issue only when Japan finally accepts the situation in northeast Asia is radically different from that of 1905.