Japan’s Flawed Case for Dokdo / Takeshima – Setting the Record Straight

The following page contains a copy of Shimane Prefecture’s Brochure stating their position on the this dispute. Dokdo Island is called Takeshima by Japan and is sometimes referred to as Liancourt Rocks by western nations. Page by page we can review Japan’s claim and determine if their position has validity. Below each page are some excerpts from the brochure followed by rebuttals or where needed, relevant data has been added. Each page can be clicked on for a larger image.

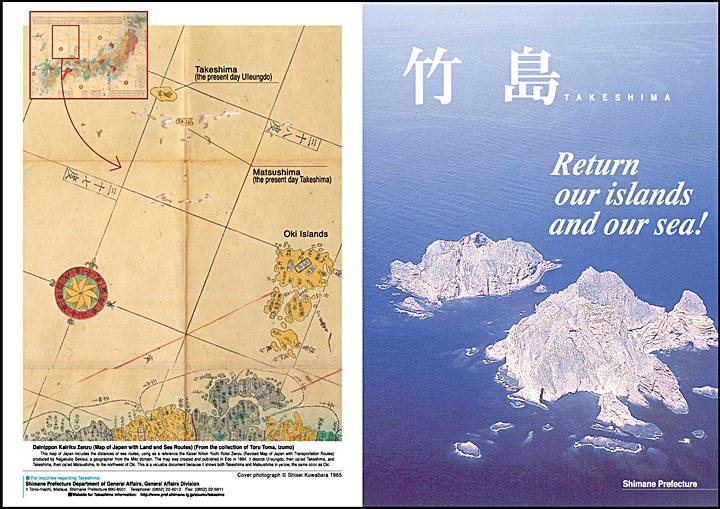

Shimane’s Prefecture’s Takeshima Brochure, Front and Back Covers

“竹島 Return our islands and our sea…Plus 400,000 sq. kms..!”

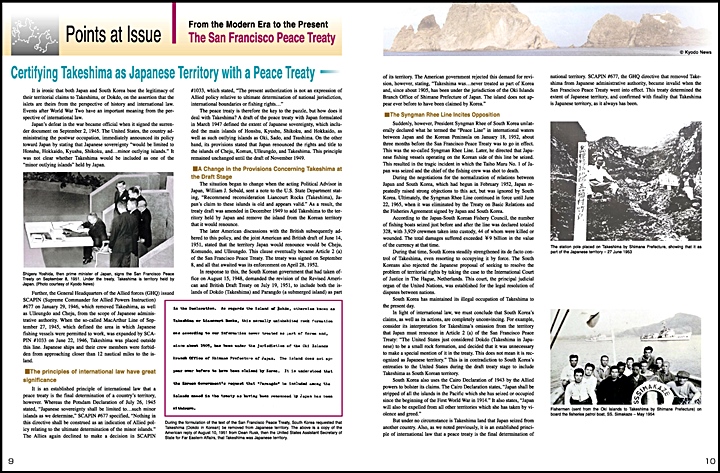

The cover title of Shimane’s flyer tells us right away what this dispute is really about. “Return our Island and the Sea” Although Japan’s MOFA attempts to make this a historical dispute about past sovereignty over Takeshima, Japan’s real motives are to acquire exclusive rights to the rich fishing grounds and potential natural gas reserves located around and under Takeshima. Moreover, the approach Japan has used regarding other uninhabited islands in her surrounding waters gives Japan’s neighbours grave concern. Case in point: The Okinotori Islands.

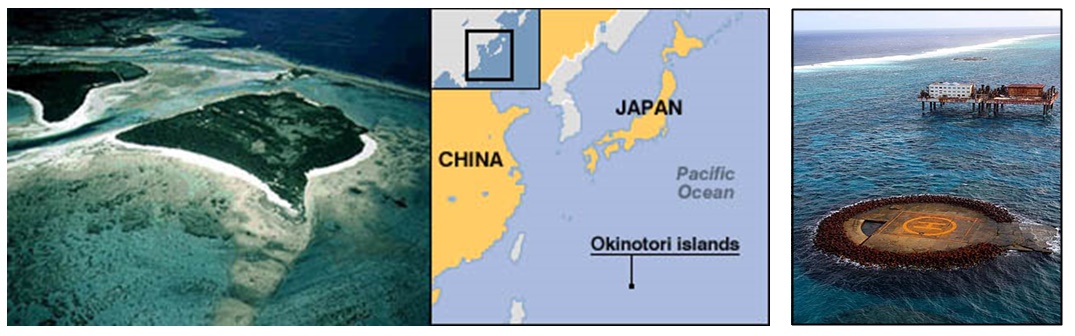

The Okinotori Islands are sometmes called the southernmost “islands” of the Japanese archipelago. These rocks been a source of contention between Japan and China since 2004, when Chinese officials started to refer to it as “rocks” not as an “island.” The waters around the reefs are potentially rich in oil and other resources and lies in an area of potential military significance. At high tide, one area of the reefs is roughly the size of a twin bed and pokes 7.4 centimeters (2.9 inches) out of the ocean. The other is the size of a small bedroom and rises about twice as high. The entire reef consists of approximately 7.8 square kilometers (3 square miles), most of which is submerged even at low tide.

Above left: Little more than rocks, Japan claims an EEZ over 154,500 square miles (400,000 km²) around Okinotorishima. International law of the sea states that “rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive economic zone.” Above right: This image shows the concrete slab surrounded by huge tetrapods to prevent erosion around Okinotorshima.

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, an island is “a naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide”. It states that “rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no Exclusive Economic Zone.” Japan signed the Convention in 1983; the Convention came into force in 1994?1996 for Japan.

However, Japan claims an EEZ over 154,500 square miles (400,000 km²) around Okinotorishima. The PRC disputes this claim, saying the area only consists of rocks and not islands.

Jon Van Dyke, a law professor, has suggested that the situation is similar to the failed British attempt to claim an EEZ around Rockall, an uninhabited granite outcropping in the Atlantic Ocean. The UK eventually dropped its claim in the 1990s when other countries objected. Dr. Dyke has further asserted that it is impossible to make, “A plausible claim that Okinotori should be able to generate a 200 [nautical]-mile zone”.[3] Tadao Kuribayashi, another law professor, disagrees, arguing in part that rocks and reefs differ in composition and structure, and that the intent of the provision was geared toward the former.

Japan’s past policy of constructing artificial islands and declaring rocks as EEZs tells us in the event she was to acquire Takeshima, the next step could very well be (as some Japanese officials have hinted) to declare or make Takeshima “habitable” or as an EEZ. This could further complicate the issue. Korea, on the other hand, has maintained uninhabitable islands cannot be designated as EEZs and allows for a 12 nautical mile zone around Dokdo. This is similar to an equidistant boundary between Korea and Japan’s nearest landfalls.

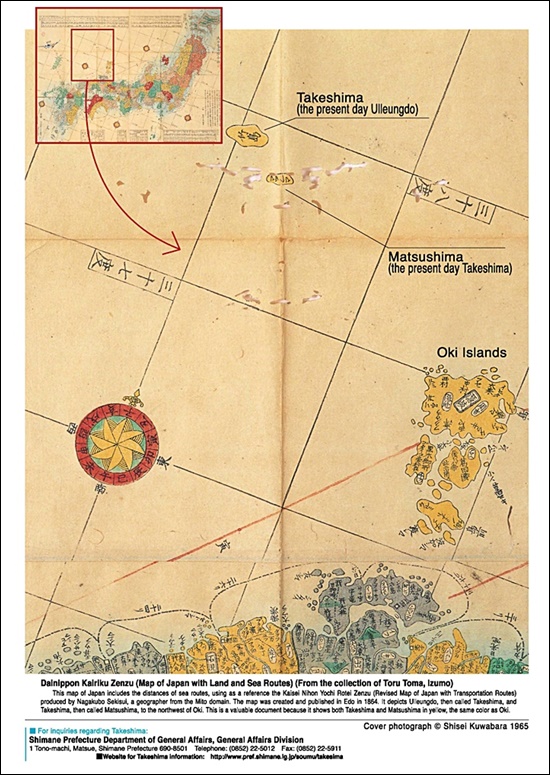

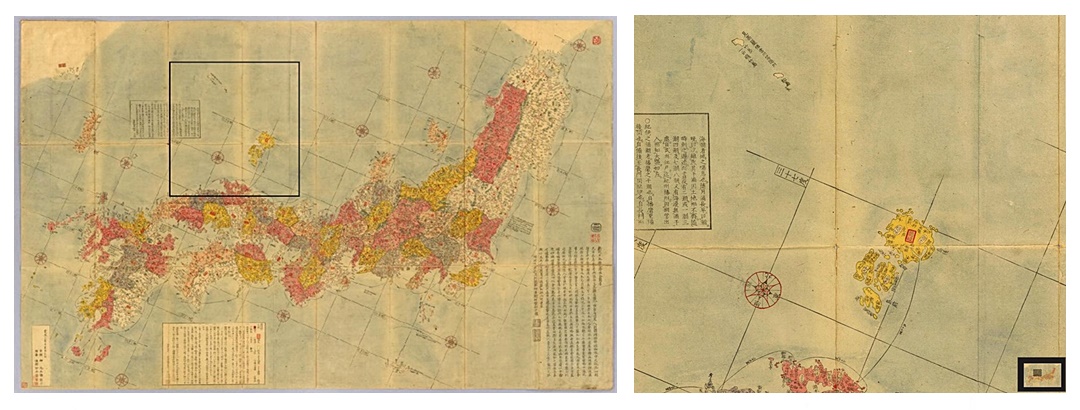

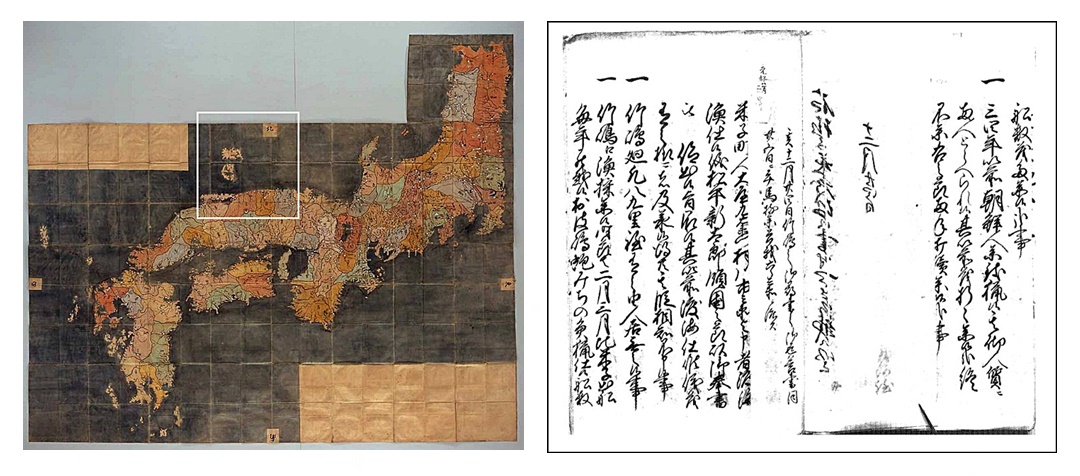

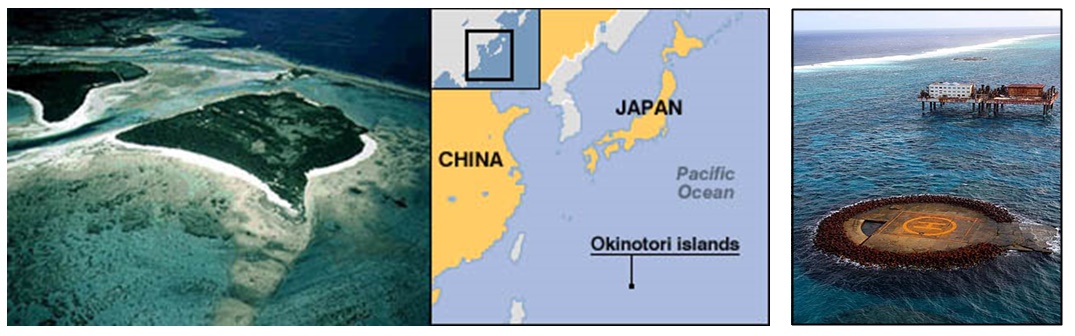

The 1864 Japanese Map on the Back Cover, Shimane’s Misleading Interpretation

“Do color-coded historical Japanese maps really show Dokdo – Takeshima as Japan’s territory..?”

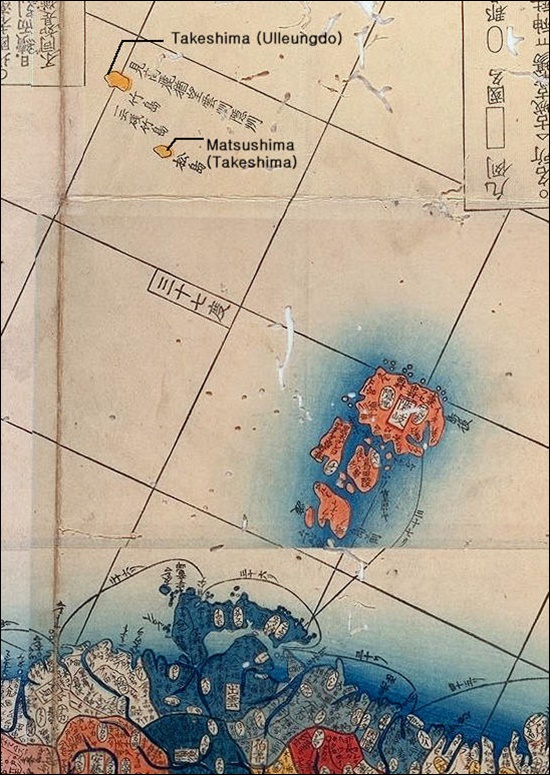

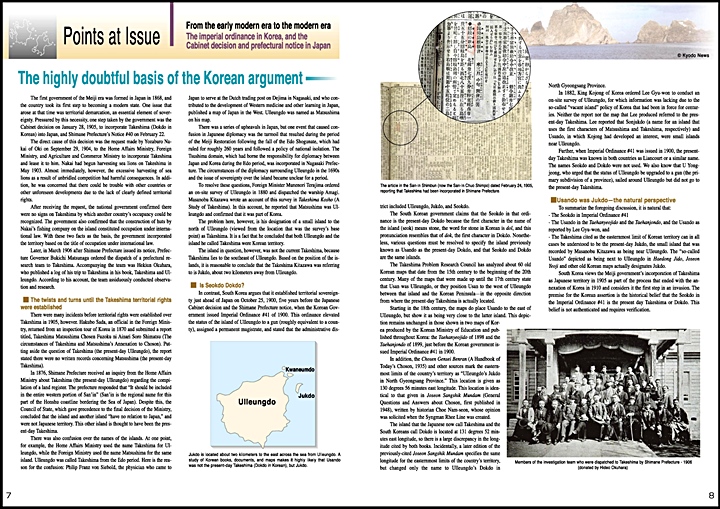

The map on the back cover of this brochure is cited because the colour of both Takeshima 竹島 (Ulleungdo) and Matsushima 松島 (Dokdo) are the same yellow colour as Japan’s Okinoshimas to the East. From here Shimane Prefecture leads us to believe in the year 1864 Japan considered both Ulleungdo and Matsushima (Dokdo) as Japanese territory. Is this true?

It is very disappointing to see Shimane Prefecture present such clear attempt to mislead the public. It severely damages the credibility of the brochure and whoever had written it. There are some facts that prove the above assertions as historically inaccurate. The map from Shimane’s brochure is on the left. To the right is a similar Japanese map Kaisei Nihon Yochi Rotei Zenzufrom the year 1775. Oki Islands are of course a different colour.

Most importantly, most, if not all, historical maps of Japan fail to include both Ulleungdo (Takeshima) and Dokdo (Matsushima) as Japanese territory. Some of these historical maps can be found at the following links.

Japanese Historical Maps of Japan Excluded Dokdo.

Shimane Prefecture’s Takeshima Brochure tries to claim the map to the left is proof that Japan considered Takeshima (Ulleungdo) and Matsushima (Dokdo) as Japanese territory. This “evidence” is easily proven false by numerous Japanese historical records and the other Japanese map to the right that shows different coloration..

A Japanese Map of Japan from 1791

A Japanese Map of Japan from 1840

The map Shimane cites above supposedly shows Takeshima (Ulleungdo) as Japanese land because Takeshima (竹島) and Matsushima (松島) are both yellow like the Oki Islands to the South. However, as we can see, almost all Japanese historical maps show them as different colours. In reality Ulleungdo- Takeshima (竹島) was “ceded” to Chosun in 1696.

Most interestingly readers should take note, all of the charts show a line indicating voyage routes from mainland Japan to Oki Islands. However, no voyage routes extend to Ulleungdo (竹島) and Dokdo (松島). This would indicate the clandestine voyages by Japan’s Oki Islanders to this region were unknown to the Japanese government.

In 1836 a Japanese were caught trespassing on Ulleungdo (then called Takeshima) and those responsible punished by the Shogunate. Later, In 1883 Japanese trespassers were forcibly removed from Ulleungdo. The number of historical references proving Ulleungdo was Korean land, are too numerous to mention in this rebuttal.

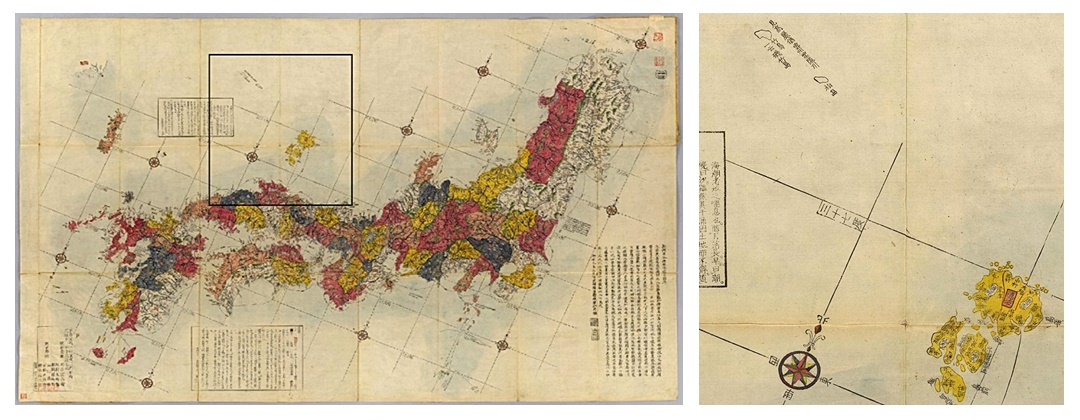

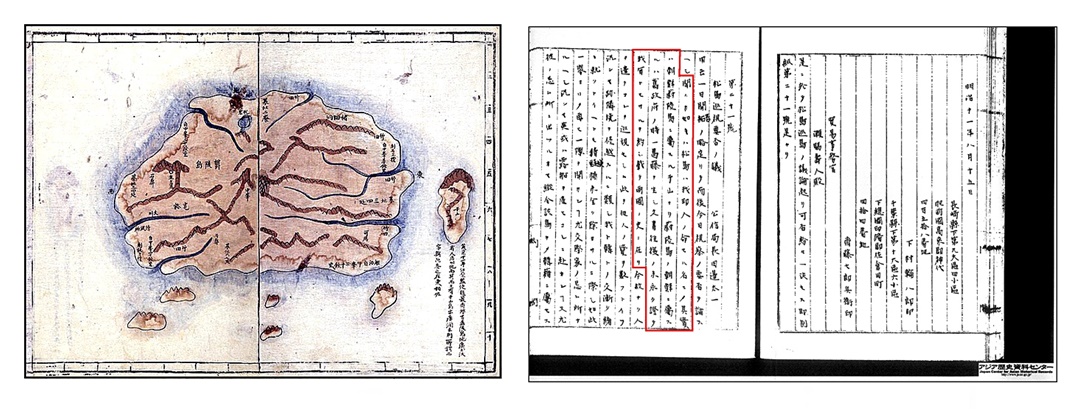

Color-Coded Reference Maps From the Trial of Hachiemon in 1836.

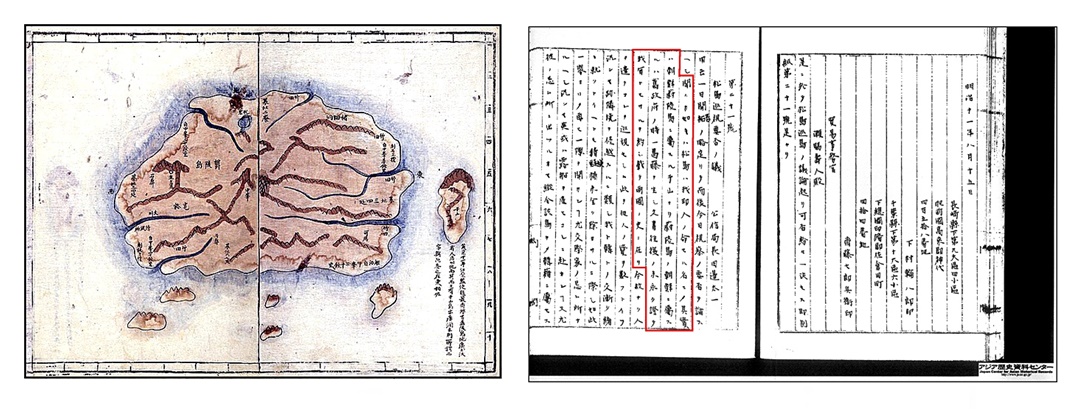

As mentioned, in 1836 a group of Japanese traders were on trial for the Ulleungdo trespassing incident. The related maps and documents prove that both Ulleungdo and Dokdo were Chosun (Korean) territory. Color-coded charts depicted both Ulleungdo and Dokdo as Korean in red and Japan as yellow. Because these maps were for reference and related to the limits of Japan and Korea, the color-coding was intended to illustrate the true definition of Korean and Japanese territory as of 1836. (see below)

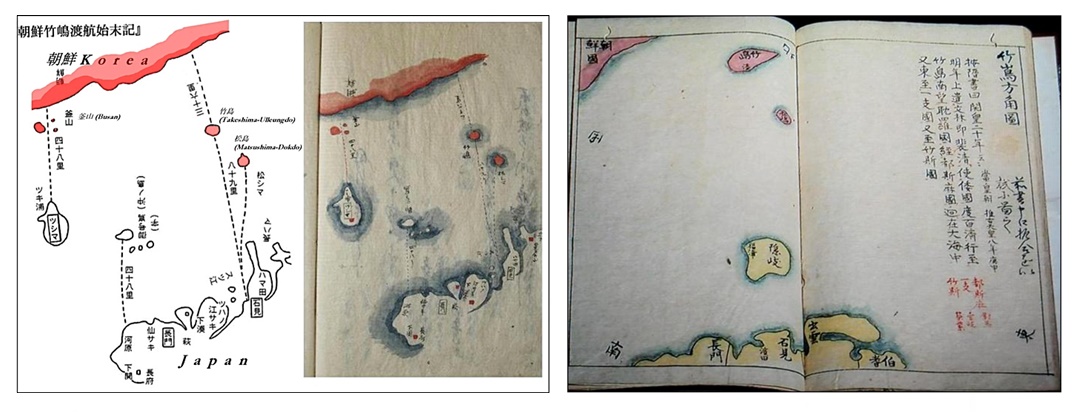

Above left: This image above is divided with labelled map for reference on the left. The original is Aizuya Hachiemon’s map drawn during the investigation of his trespassing on Korea’s Ulleungdo Island (Takeshima 竹島). This map clearly shows Ulleungdo (竹島) and Dokdo (松島 ) as Chosun (Korean) land. Above right: Another map from the Aizuya Hachiemon case showing Dokdo as Korean.

The 1836 Hacheimon Ulleungdo Trespass Incident

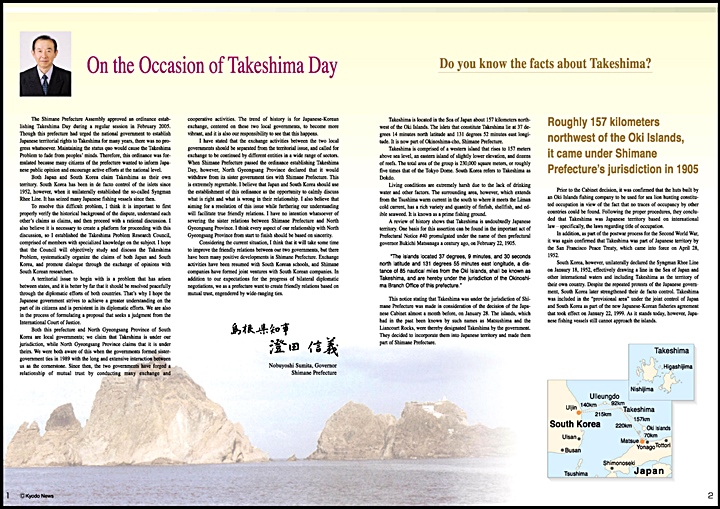

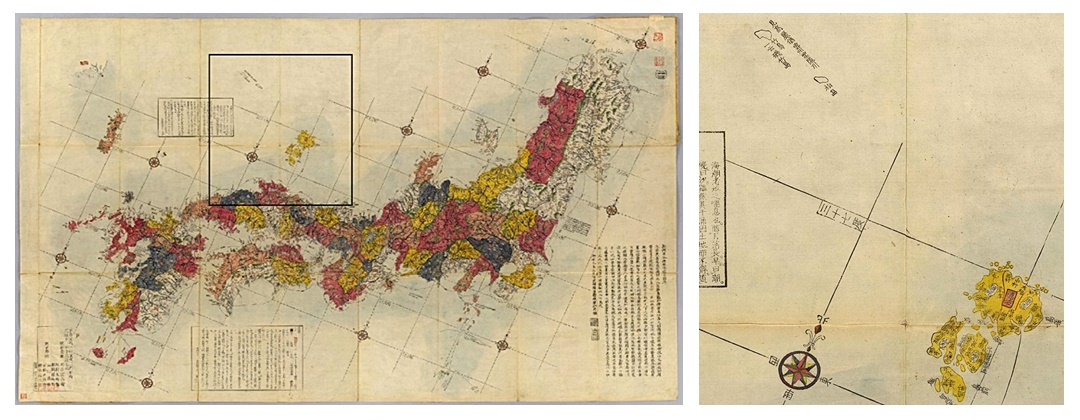

“The Occasion of Takeshima Day..?” – Japan’s Selective Memory of Historical Events

“Why did Japan annex Dokdo – Takeshima in 1905..?

The Governor of Shimane, starts off with a logical introduction. He states “To resolve this difficult problem, I think it’s important to properly verify the historical background of the dispute, understand each other’s claims, and then process with a rational discussion…” These words ring hollow when as we read further. The Japanese government is still in a state of denial regarding both the origins of the Takeshima problem and the true nature of Japan’s incorporation of the islets.

In describing Japan’s 1905 incorporation of Takeshima, Shimane’s governor states

“The islands which had been known by such names as Matsushima and Liancourt Rocks were thereby designated as Takeshima by the government. They decided to incorporate them into Japanese territory and made them part of Shimane Prefecture…”

Governor Nobuyoshi Sumita, not surprisingly, makes no mention that the Japanese Navy surveyed the islets for building military watchtowers months before the incorporation. There is no mention the Russo~Japanese War was raging in China, besieged Port Arthur (Dalian) had just fallen and Admiral Togo’s Fleet waited to engage Russia’s approaching Baltic Fleet in the Tsushima Straits. These events all occurred as Japan quietly annexed Takeshima. The announcement little more than a whisper at regional government levels.

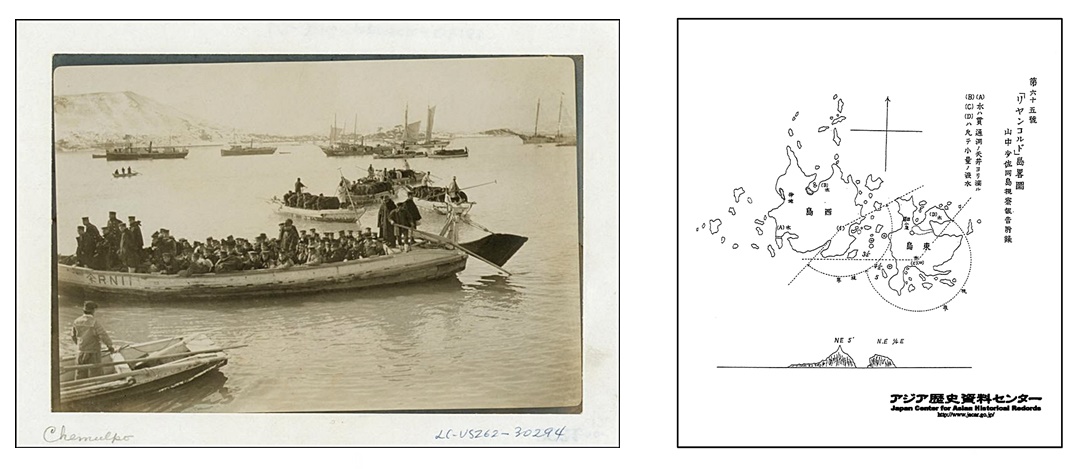

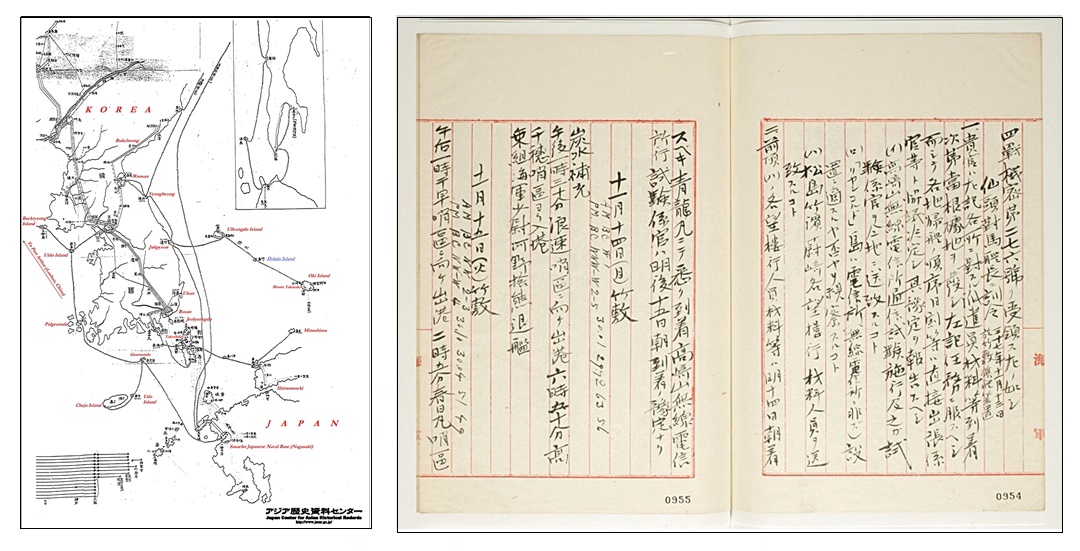

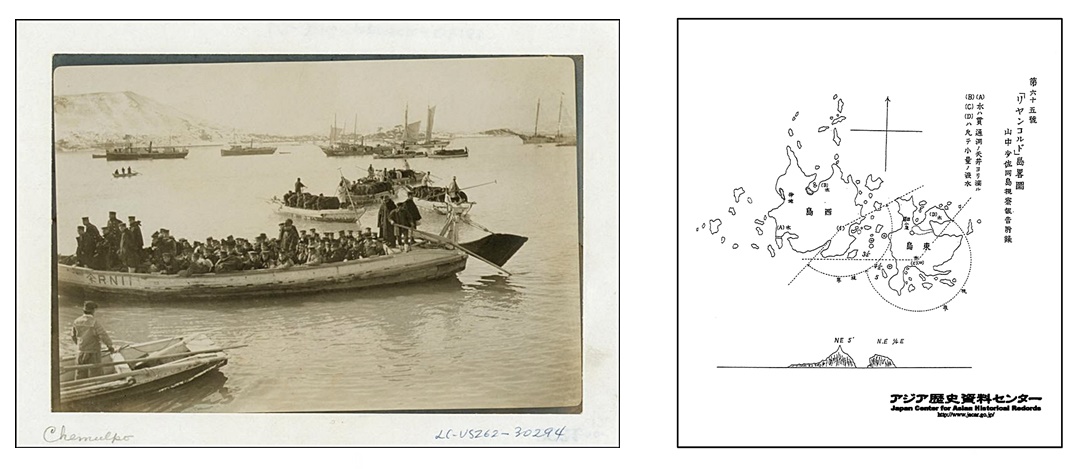

Above left: Japanese troops landing in Chemulpo (Korea’s Incheon) in February 1904. Above right: Three months before Japan incorporated Takeshima, Yamanaka Shibakichi of the Japanese Warship Tsushima drew this survey map of Liancourt Rocks. Drawn during the Russo~Japanese War, it shows ideal watchtower locations and visibility ranges for military observation point and telegraph station. (click)

This brochure’s candy-coated version of Japan’s Incorporation of Takeshima into Shimane Prefecture doesn’t deceive those who have even rudimentary knowledge of history in Korea and northeast Asia at the turn of the 20th Century.

On February 8th 1904 the Japanese Navy opened a surprise attack on Russian boats Varyag and Korietz anchored in Chemulpo (Incheon). Their troops continued to advance into Seoul and after weeks of continued intimidation and manipulation, the Koreans signed the February 24th, Japan-Korea Protocol.

The protocol allowed the Japanese to occupy strategic areas of Korea. Immediately the Japanese Army and Navy began constructing military observation and communications posts on all strategic coastal and island locations of Korea. These areas included: Uldo Island, Cheju Island, Udo, Hongdo, Palpo, Wonsan, Jukpyeon, Ulsan, Jinae, Geomun Island, Baekryoeng Island, Ulleung Island, Pohang, and Pusan.

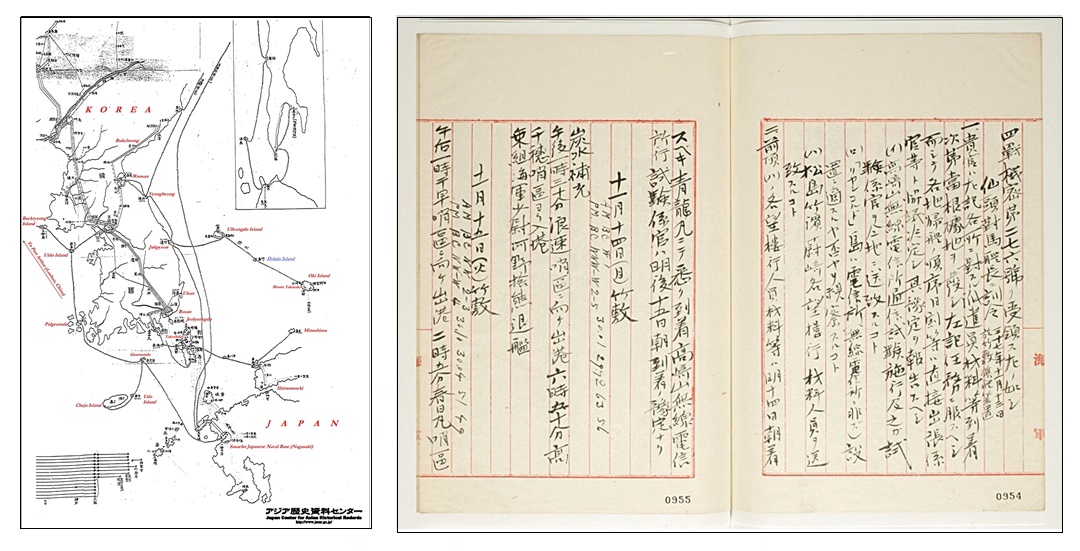

Above left: A Japanese Naval Map of June 1905 during Russo-Japanese War shows the Japanese military telegraph lines between Japan and Korea in June 1905. The wavy line from Oki to Korea through Liancourt Rocks and Ulleungdo (Matsushima, 松島) indicates the lines. Above right: While in the process of installing military watchtowers on Korean land, the Japanese warship Tsushima’s logbook (above) records the command to survey Liancourt Rocks for telegraph installation on November 13th 1904, three months before the island was annexed.

The Japanese government refuses to acknowledge the link between her colonial ambitions in Korea and the annexation of then Liancourt Rocks. The logbooks of the Japanese warship Tsushima tell us otherwise.

The Japanese Warship Tsushima was issued special directive #276 on November 13th 1904. It included three instructions: a)Inform of the test of the wireless telegraph communications of Takasaki Mountain (on Oki Island) along with the test technician. b)Survey Liancourt Rocks (Dokdo Island) for its suitability for telegraph installation (not wireless telegraph) c)Dispatch workers and materials for Matsushima, (Ulleungdo) Jukpyeon, and Cape Ulsan watchtowers.

These instructions alone demonstrate Japan’s military activities during the Russo~Japanese war are inseparable part of the annexation of Dokdo Island.

Japan’s Takeshima X-Files – 1

Japan’s Takeshima X-Files – 2

Japan’s Takeshima X-Files -3

Shimane’s Incorrect Interpretation of the Takeshima Dispute’s Origin

“When did the Dokdo – Takeshima dispute really begin..?”

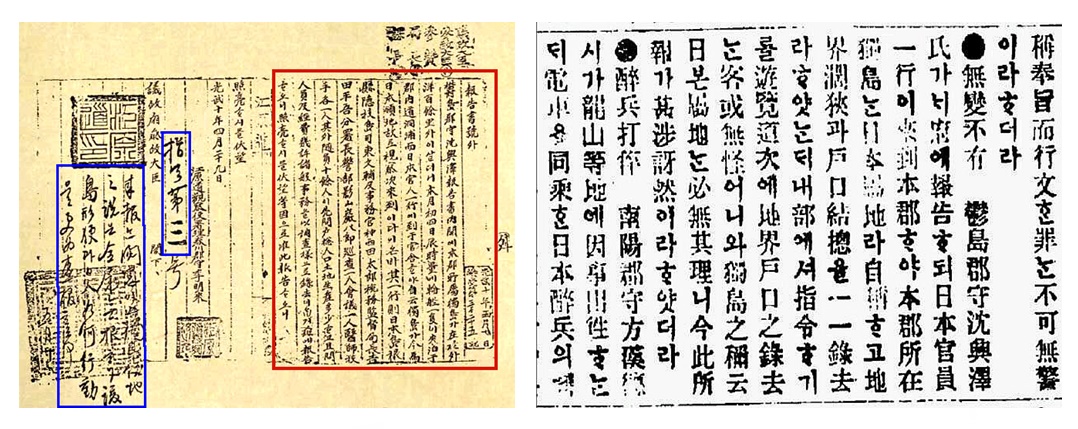

On page three of this brochure reads “…It is commonly known that the Takeshima problem originated with the South Korean government’s establishment of the so-called Syngman Rhee Line on January 18th 1952…” This is proven wrong by Governor Nobuyoshi Sumita himself on the next page. He quotes “In 1906 when Shimane Prefecture government officials visited Ulleungdo after inspecting Takeshima, Uldo Magistrate Shim Heung Taek reported to the governor of the Korean province “Dokdo is part of Ulleungdo” ie Dokdo belonged to his county.

The Japanese Government clandestinely annexed Dokdo Island in a sub rosa cabinet meeting. This was without external notification beyond a minuscule ad on a second page of a local newspaper that didn’t even mention the island’s name.

Furthermore, the Korean government contested Japan’s annexation of Dokdo at different governmental levels and through local media immediately upon being informed in 1906. However, by this time, the Japanese had assumed control over Korea’s foreign affairs office.

The above records show that upon hearing Japan annexed Dokdo, Korea contested this action through both her government and media. By this point Korea’s Foreign Affairs Office had been dismantled starting in August of 1904.

Korean Objections to Japan’s 1906 Annexation of Dokdo – Takeshima

There is a whole page of this brochure dealing with Japan’s dispute over Korea’s declaration of the Syngman Rhee Line on January 18th 1952. Yet there isn’t one sentence addressing Korean contentions that Dokdo was her territory in 1906. In other words, the Takeshima – Dokdo dispute only became an problem when Japan contested and Korea’s objections in 1906 mean nothing. Shimane’s brochures so-called “Objective Investigation of the Facts” doesn’t deliver.

The valid point Shimane makes was that the Oyas and Murakawas were given permission to voyage to Takeshima and Matsushima upon accidentally finding the islands in 1618. However, the brochure tries to take these historical references a step further by stating “Matsushima was known as part of Japan”.

“Was Dokdo Takeshima part of Japan during the 17th Century..?”

The Japanese Shogunate answered this very same question to Tottori (Shimane) Prefecture in 1695 while trying to determine the status of Takeshima (Ulleungdo) and Matsushima. It was stated in this correspondence that the islands were not part of Tottori or Inbashu. On page six of this brochure Japan argues that even if Takeshima (Ulleungdo) and Matsushima were not part of these prefectures is does not mean they were excluded from Japan. It’s not clear what they mean.

Above left: Tottori Province’s response to the Shogunate confirmed that Takeshima and Matsushima were not part of Inbashu or Hoki districts in 1695. Above right: A 1654 Japanese map of Japan. Takeshima and Matsushima are not included as part of Japan and as always, Oki Islands are the Northwestern limit of Japan.

Some Japanese historians have long maintained that the Shogunate bestowed Takeshima (Ulleungdo) and Matsushima (Dokdo) to the Murakawa and Oya families during the 17th Century. Both of these families resided in Yonago City and their annual voyages to (illegally) gather Ulleungdo’s resources departed from Yonago. Thus, if these two islands were indeed “bestowed” to Murakawas or Oyas it would have been considered part of Tottori Yonago City if at all. However, this is shown not to be the case here. The Japanese Government’s official stance regarding this record on page six is “This does require future investigation in the future…”

We can also determine if Japan thought Takeshima (Ulleungdo) and Matsushima were part of Japan by citing maps of the 17th Century. Japanese maps of this era consistently show the Okinoshimas as the northwest boundary of Japan. A typical map from this time can be found on the right, above this text.

The Japanese 1695 Bafuku Records

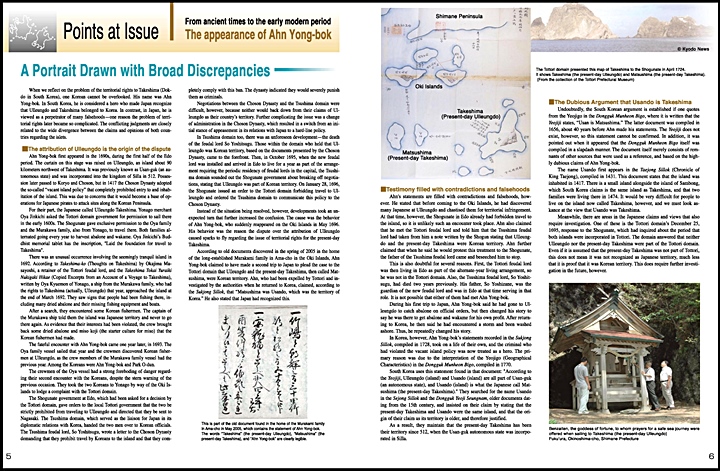

Shimane’s Poorly Researched Analysis of the Anyongbok Incident

Shimane Prefecture’s Omission of Historical Data

The first point that should be made is the term the “Anyongbok Incident” is a misnomer. In 1696 Anyongbok voyaged to Japan accompanied by 10 other men, five were said to be Buddhist monks. They were all unarmed and peacefully disputed Japan’s trespassing on Ulleungdo, an island known as Korean territory since the 6th Century.

There are some discrepancies in the historical records of this incident to be sure. However rather than take an academic approach, Japanese scholars chose to disregard this valuable data. It’s not surprising there are some facts that don’t add up, the records of the dispute are hundreds of years old and recorded by two different nations. Some points need to be addressed because Japan’s Takeshima brochure falls short of being objective.

There is a brief mention of the 2005 Murakawa records of the Anyongbok Incident that was discovered but some very crucial data was omitted.

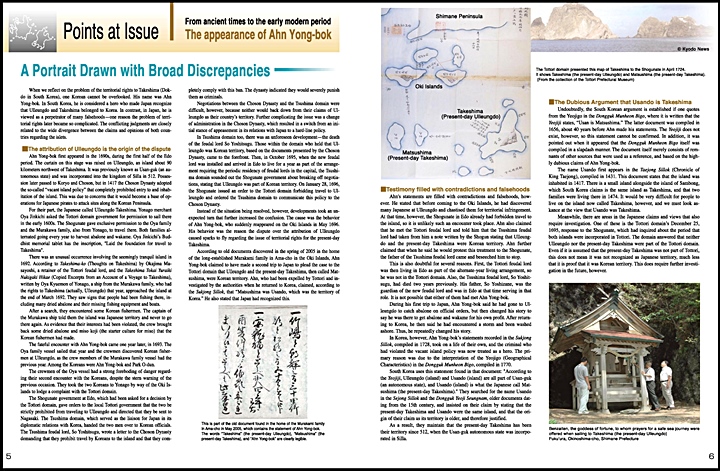

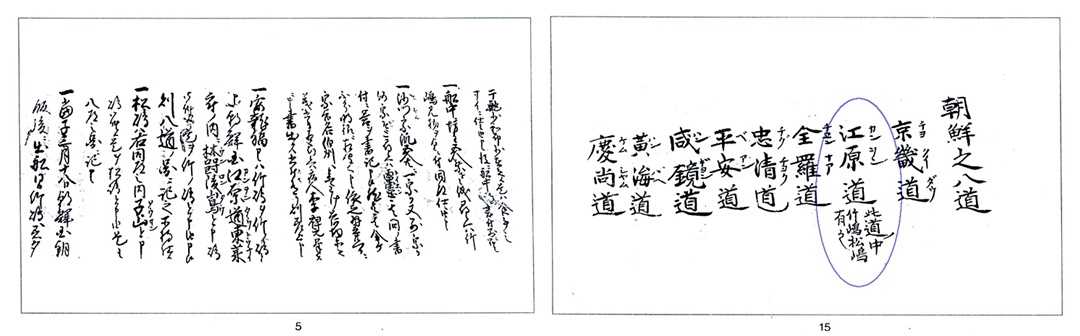

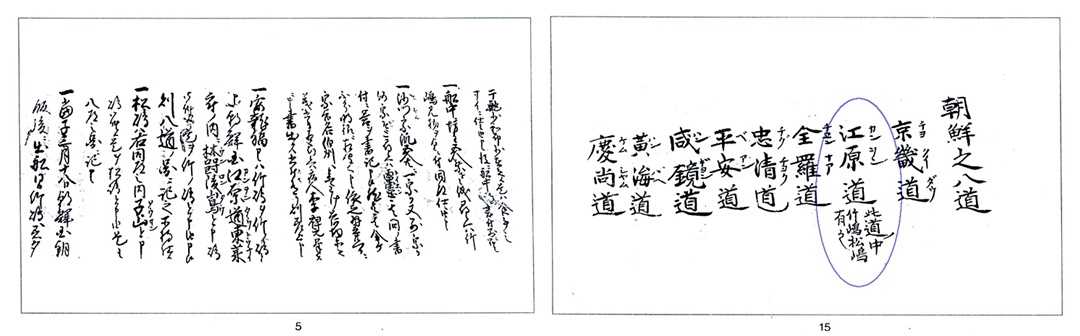

The Shimane Brochure seems to concede the islands in this dispute were indeed Takeshima (Ulleungdo) and Matsushima (Dokdo). Page five of the newly discovered Murakawas records read as follows:

According to Anyoengbok: “Takeshima (Ulleungdo) is this Bamboo Island. He says that there is an island named Ulleungdo in Dongnae-bu, Gangwando, Korea and this is also called Bamboo Island. He had a map of eight provinces of Korea that says so. Matsushima (Dokdo) is the island called Jasan (Usan) in the same province of Gangwando. It is the same name for Matsushima (Dokdo) and this is also recorded on the eight provinces of Korea map..”

Above left: The 2005 Murakawa documents record An Yong Bok claimed Matsushima (Dokdo) was Usando and thus Chosun land. Above right: An Yong Bok’s “map” of Korea, shows Takeshima (竹島) and Matsushima (松島) as part of Gangwan Province (江原道)

Anyongbok stated that Jasando (Usando) was Matsushima (Dokdo) in this record. Later in this document he records the distance as about 50 ri. This distance, like most Japanese maps of the day is quite inaccurate. However, it is much too distant to be any of Ulleungdo’s neighbour islands. Included in these records was a map or chart that listed all of Korea’s provinces. Under Gangwan Province (江原道) the names Takehima (竹島) and (松島) can clearly be seen.

This record is an important piece of evidence in verifying the identity of Usando. But it raises another important question. If Japan’s shogunate considered Matsushima as part of Japanese territory why didn’t they object to Anyongbok’s claim? After this incident the issue of Takeshima and Matsushima was never raised again. It’s a valid point to say Japan’s silence to Anyongbok’s claim to Matsushima amounts to acquiesence.

An Yong Bok and Dokdo Island

The Confusing Issue of Usando Island

Both sides of the Dokdo – Takeshima dispute have used the issue of Usando Island to bolster their case. The identity of Usando can differ from the historical reference that is cited. Given the distance of Anyongbok’s Usando (Matsushima) 50 ri from Ulleungdo this Usando cannot be Jukdo Islet located only 2.2kms from Ulleungdo’s shore. This “Usando” would be best translated as todays Dokdo.

Chosun maps are often used to as proof that Usando is Jukdo Islet because it is located close to Ulleungdo’s shore on these charts. Citing these maps is problematic because they all seem to show five large non -existent inlands on the southeast shore of Ulleungdo. There are no such islands located is this position. It’s very curious that all of these maps show these non existent islands. The only conclusion is these maps were copied through the ages and the “phantom islands” added on.

Above left: Historical Chosun maps of Ulleungdo show the island as about three times too large and consistently show non existent islands on the islands South shore. Above right: Some Japanese historians of the 19th Century concluded Usando was Matsushima (Dokdo) and appended to Ulleungdo.

Another trait of these maps is the phrase “The So-called Usando” drawn on the island depicted on these maps. This raises the question why wasn’t the island simply labelled as “Usando”? The phrase leads us to believe Chosun was trying to again familiarize themselves with the area after a long absence.

The Ulleungdo Island region endured a period of neglect after Chosun initiated a vacant island policy on Ulleungdo. This was due to repeated invasions by Japanese pirates and the devastating effects of the Imjin Wars. After the Anyongbok incident occurred in the late 17th Century, there was renewed interest in Ulleungdo and new surveys were undertaken. Thus the term “The So-Called Usando” began to be seen on late 17th Century maps but it’s not clear if these maps are the Usando of ancient times.

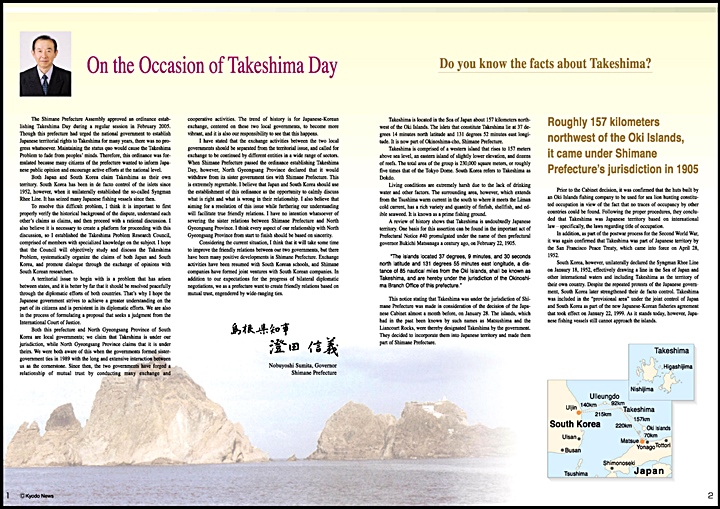

Shimane’s Interpretation of the Japan Peace Treaty – Post WWII and Dokdo

“Did Allied Command really grant Dokdo – Takeshima to Japan after World War Two..?”

The Treaty of San Francisco or San Francisco Peace Treaty between the Allied Powers and Japan, was officially signed by 49 nations on September 8, 1951 in San Francisco, California. It came into force on April 28, 1952. It is a popularly known name, but its formal English name is Treaty of Peace with Japan. Jon M Van Dyke summarizes the negiotiation process very well in his article describing the Dokdo – Takeshima problem it states:

“…The negotiations involving the fate of former Japanese territories was a long, drawn-out process. The first five and seventh drafts of the treaty provided that Liancourt be given to Korea by including the islets in the Article 2(a) list. The sixth, eighth, ninth, and fourteenth drafts explicitly stated that the territory of Japan included Dokdo Takeshima. The tenth through thirteenth and fifteenth through eighteenth drafts, like the final draft, were silent on the status of Dokdo Takeshima…”

“…In the end there was no mention of Liancourt Rocks in the San Francisco Peace Treaty. The allied powers did not indicate why they chose to remain silent on the outcome, but the varying positions taken during the deliberation process indicate that the decision was made either because not enough information had bee provided regarding the historical events surrounding Japan’s incorporation of Dokdo Takeshima or because the Allied Powers felt themselves incapable or inadequate adjudicators…”

Shimane Prefecture interprets the San Francisco Peace Treaty from a very narrow perspective. That being, Japanese Takeshima lobbyists rely heavily on American confidential memorandums exchanged during the negotiation process. (Dean Rusk) Let us remember first these were confidential documents that never saw the pages of the treaty itself. We must also consider there were 48 other nations involved in the deliberation process. This leads us to believe some other countries did not concur with U.S. foreign policy toward Dokdo Takeshima. Some classified documents show the U.K. preferred to maintain a boundary separating Korea and Japan similar to previous SCAP directives.

What factors influenced allied negotiations during the San Francisco Peace Treaty?

To comprehend what factors played a role in Supreme Allied Commands decision process, again historical context helps us understand. While the San Francisco Peace Treaty was being negotiated, the Korean peninsula was engaged in the Korean war. At one point the situation on the Korean peninsula had deteriorated for the worse and communist North Korea had captured all but the Busan area. The allies, with good reason, were concerned the entire Korean peninsula would fall to the communist North.

In the event Korea become communist, it would be detrimental to the allies if Dokdo Takeshima were part of a united communist Korea. This would essentially give an unfriendly nation the ability to monitor and control naval activity in the East Sea (Sea of Japan) much as the Japanese did during the Russo Japanese War of 1904~1905.

When the Cold War started, America and her allies were in the process of militarily posturing against Russia and China. Staunch anti-communist politicians such as Dean Rusk were involved in the negotiations over Takeshima. It is Dean Rusk’s confidential memorandums that Japan cites in their argument over Takeshima. Who was Dean Rusk?

Dean Rusk was involved in military affairs throughout his life and political career. In World War II he joined the infantry as a reserve captain (he had been a ROTC Cadet Lieutenant Colonel), Rusk served in Burma as a staff officer and ended the war as a colonel with the Legion of Merit and Oak Leaf Cluster.

Dean Rusk returned to America to work briefly for the War Department in Washington. He was made Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs in 1950 and played an influential part in the US decision to become involved in the Korean War.

As Secretary of State, Dean Rusk was consistently hawkish, a believer in the use of military action to combat Communism. During the Cuban missile crisis he initially supported an immediate military strike, but he soon turned towards diplomatic efforts. His public defense of US actions in the Vietnam War made him a frequent target of anti-war protests.

It’s not an exaggeration to say Dean Rusk’s military background deeply effected his political decisions and his policy on Dokdo – Takeshima was no exception. American policy on Dokdo – Takeshima was just a reflection of her military policy in Northeast Asia during the Korean/Cold War.

In this exchange it can be read Dean Rusk supported Japan’s claim to Dokdo Takeshima. However, as we continue to study more American records from the Japan Peace Treaty archives we will see these papers do little more than show U.S. decisions on territorial ownership were based largely on military strategy.

It should also be noted, The Rusk Papers were confidential memorandums. None of Rusk’s opinions were made public nor conveyed to the Japanese government. In fact, they weren’t made public until decades later. Thus, the Rusk papers never materialized in official U.S. support for Japan’s claim to Dokdo. Rusk’s views were just one phase of America’s policy toward Dokdo that would later change into a neutral stance on the issue.

A couple of previously classified records give us an insight into the decision process the allies used to define Japan’s territorial limits. Did the allies conduct a thorough historical study of Korea before they made their decisions? Were the San Francisco Peace Treaties territorial determinations sincere representations of true historical ownership?

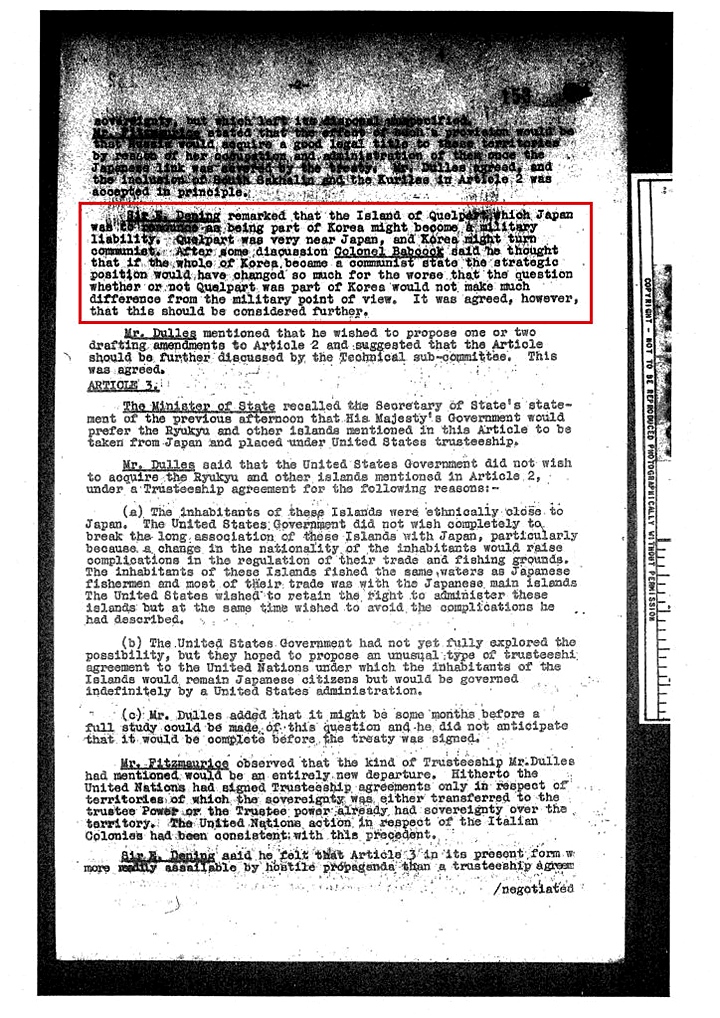

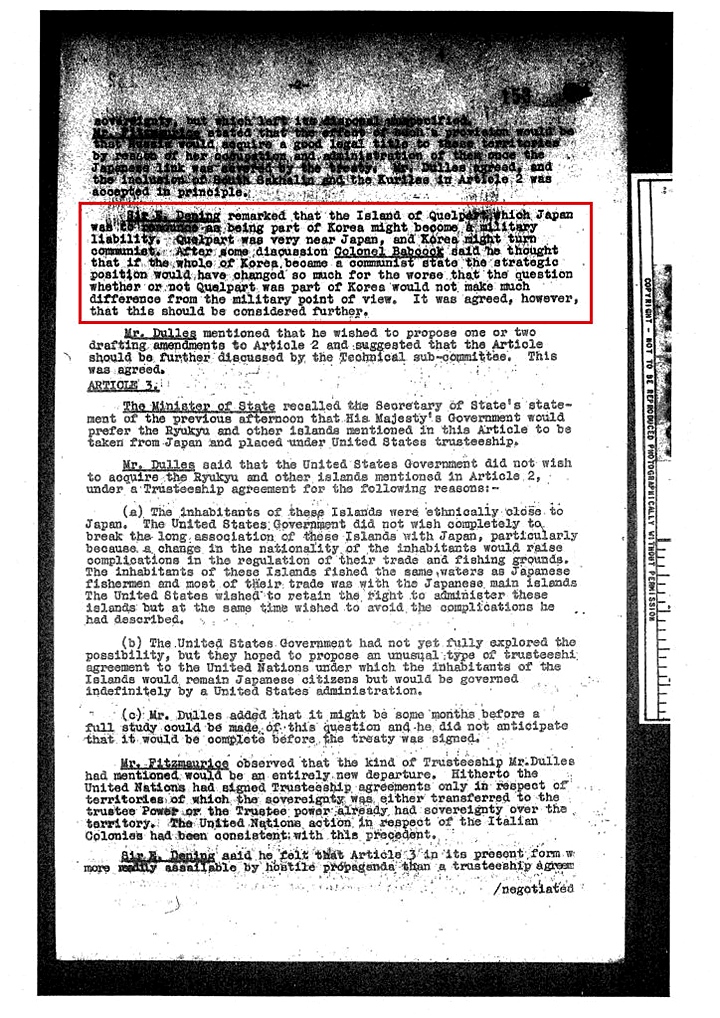

The following image is a summarized meeting record between allied commanders during the negotiation process of the San Francisco Peace Treaty. Although this portion isn’t related to Takeshima it shows how the allies deliberated before reaching their decisions. This conversation describes the situation on Cheju Island (Quelpart) This island, located south of the Korean peninsula, was indisputably Korean land. However, as this documents shows, the allies considered giving the Cheju Island to Japan for fears the Korean peninsula would fall to communist forces creating a military disadvantage.

The document states,

“Sir Dening remarked that the Island of Quelpart (Chejudo) which Japan was to renounce as being part of Korea might become a military liability. Quelpart was very near Japan, and Korea might turn communist. After some discussion Colonel Babcock said that he thought that if the whole of Korea became a communist state the position would have changed so much for the worst that the question of whether or not Quelpart was part of Korea would not make much difference from the military point of view. It was agreed however this would be considered further…”

As this document shows, military strategy of Allied Forces was a top priority when they drew territorial limits of Korea and Japan during the San Francisco Peace Treaty negotiations process.

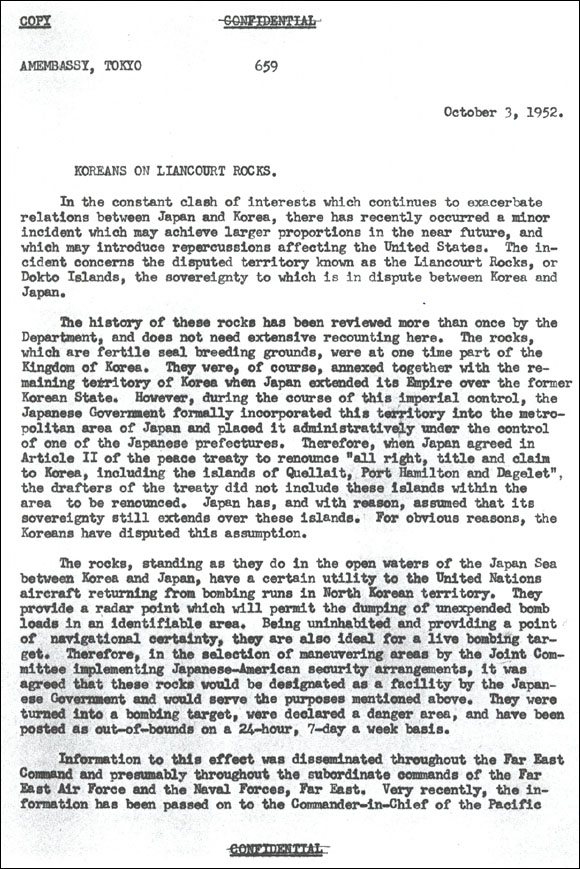

The next paper shows some American politicians at the time considered Korea’s historical claim as valid. Writing on behalf of Ambassador to Japan, Robert Murphy, the First Secretary of the American Embassy in Tokyo, John M. Steeves, writes Despatch No. 659 entitled “Koreans on Liancourt Rocks, concerning the September 15 bombing incident, when the U.S. accidentally bombed some Koreans fishing on Liancourt Rocks.

Steeves provides a short history on the sovereignty of Dokdo as follows:

“…The history of these rocks has been reviewed more than once by the Department, and does not need extensive recounting here. The rocks, which are fertile seal breeding grounds, were at one time part of the Kingdom of Korea.They were, of course, annexed together with the remaining territory of Korea when Japan extended its Empire over the former Korean State…”

However, it this case it seems the needs of the Americans and Allied Command took precedent over Korean assertions Liancourt was Chosun land. It also shows why Liancourt Rocks were designated as a facility of the Japanese government earlier. The second half of Steeves report reads:

“…The rocks standing as they do in the open waters of the Japan Sea between Korea and Japan have a certain utility to the United Nations aircraft returning from bombing runs in North Korean territory. They provide a radar point which will permit the dumping of unexpended bomb loads in an identifiable area. Therefore in the selection of maneuvering areas by the Joint Committee implementing Japan America security arrangements, it was agreed these rocks would be designated a facility by the Japanese Government and would serve the purposes mentioned above…”

The Japanese side then resorts to the San Francisco Peace Treaty, which did not mention Tokdo as one of the islands expressly excluded from Japan’s territory. Article 2 of the Treaty simply states that “Japan, recognizing the independence of Korea, renounces all right, title and claim to Korea, including the Islands of Quelpart, Port Hamilton and Dagelet.” From this perspective, the Japanese side argues that the absence of any reference to Tokdo in the San Francisco Peace Treaty, the final verdict on what constitutes Japan’s territory, implies Tokdo’s reversion to Japan.

In direct contradiction to Japan’s argument, the rational interpretation of all the post-war instruments would lead to the conclusion that, unless any express decision provides otherwise, SCAPIN No.677 would take precedence. The Peace Treaty’s mere omission of mentioning Tokdo as part of Korea’s territory does not amount to the cession of Tokdo to Japan. And a fair interpretation would be that the islands mentioned in Article 2 of the Peace Treaty should be illustrative rather than enumerative given the large number of islands scattered around the Korean Peninsula. Even if its absence of any reference causes various interpretations over the status of Tokdo, this would by no means alter the illegality of Japan’s 1905 incorporation measure.

Dokdo – Takeshima and The Truth of the Japan Peace Treaty (San Francisco Peace Treaty)

Shimane Prefecture’s Case for Takeshima – Why Their Demands Are Unacceptable

“Japan and Korea can’t use the historical circumstances of 1905 to resolve this modern dispute…”

When we study Japan’s case for Takeshima up and close and over a long period of time it becomes apparent the stance of Japan’s MOFA has gone through an evolution of sorts. Not so long ago the Japanese government’s homepage declared Matsushima was an island that was bestowed upon the Oya and Murakawa families in the 17th Century. Historical records were found that shown this not to be the case. Thus, their website no longer takes this stance. For years, the Japanese government insisted Liancourt Rocks was incorporated as “terra nullius” or no-man’s land. Recently colonial-era terra nullius land claims have been challenged and carry little weight, and Japan again changed their stance.

These days, it seems the Japanese have shifted their position to attacking Korean historical claims and desperately clinging to their dubious 1905 Shimane Prefecture Inclusion. But does the 1905 annexation of Dokdo make sense in this era? The geography of the region hasn’t changed of course but what about Korea’s political and economic situation in the 21st Century? What relevance does Japan’s 1905 annexation have in today’s modern, peaceful northeast Asia?

When Japan annexed Liancourt Rocks in 1905 Korea’s political and territorial integrity had been seriously compromised. Japanese troops occupied the whole peninsula. Korea’s Ulleungdo Island had three Japanese military watchtowers and a sizeable military presence there. Russian and Japanese forces were fighting tooth and nail in the largest war fought to the day for the exclusive right to colonize the Korean peninsula. Japanese boats plied coastal areas of Korea at will and plundered Chosun waters. Through various coerced and unequal treaties, Japan had “acquired” numerous interests in Korea. Chosun’s cabinet had lost its foreign office and the ability to conduct state to state affairs. Korea’s courts were purged of all officials opposed to Japanese policy. It was during the turmoil of this era that Liancourt Rocks was silently annexed.

Above left: This image is a photo of Korea’s Ulleungdo from Dokdo Island. Above right: A photograph of Dokdo Island from Korea’s Ulleungdo Island. Throughout the ages, these mutually visible islands were considered sister islands or appended to each other by Japanese and Koreans alike.

Today of course, Korea is a free and independent country. Ulleungdo Island has over 10,000 residents who base their livelihoods on both tourism and fishing Ulleungdo’s surrounding waters. Needless to say, these activities extend to Ulleungdo’s most proximate island, Dokdo. Therefore from this modern economic standpoint alone, it makes little sense Japan should extend her boundary 160 kms westward and encroach within visual proximity to Korea’s Ulleungdo.

Japan’s claim for Dokdo has no place in modern Asia. The territorial demands Japan makes are totally out of line with the real, political situation in the East Sea (Sea of Japan) today. If and when a settlement on this issue is proposed, the national limits drawn must fairly represent the interests of both Japan and Korea here and now. An international boundary should be based on the premise that Korea is equal to Japan not on the past expansionist-era relationship between colony and colonizer. If Japan maintains the same outdated position as in the brochure above, it is unlikely a resolution will be reached in the foreseeable future.

Dean Rusk was involved in military affairs throughout his life and political career. In World War II he joined the infantry as a reserve captain (he had been a ROTC Cadet Lieutenant Colonel), Rusk served in Burma as a staff officer and ended the war as a colonel with the Legion of Merit and Oak Leaf Cluster.

Dean Rusk was involved in military affairs throughout his life and political career. In World War II he joined the infantry as a reserve captain (he had been a ROTC Cadet Lieutenant Colonel), Rusk served in Burma as a staff officer and ended the war as a colonel with the Legion of Merit and Oak Leaf Cluster.

The document states, “Sir Dening remarked that the Island of Quelpart (Chejudo) which Japan was to renounce as being part of Korea might become a military liability. Quelpart was very near Japan, and Korea might turn communist. After some discussion Colonel Babcock said that he thought that if the whole of Korea became a communist state the position would have changed so much for the worst that the question of whether or not Quelpart was part of Korea would not make much difference from the military point of view. It was agreed however this would be considered further…”

The document states, “Sir Dening remarked that the Island of Quelpart (Chejudo) which Japan was to renounce as being part of Korea might become a military liability. Quelpart was very near Japan, and Korea might turn communist. After some discussion Colonel Babcock said that he thought that if the whole of Korea became a communist state the position would have changed so much for the worst that the question of whether or not Quelpart was part of Korea would not make much difference from the military point of view. It was agreed however this would be considered further…”

Steeves provides a short history on the sovereignty of Dokdo as follows:

Steeves provides a short history on the sovereignty of Dokdo as follows: