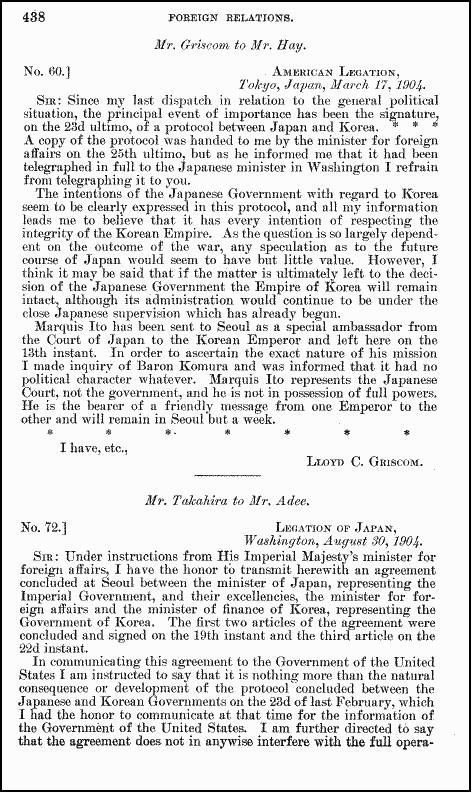

A falsehood perpetuated by Japan’s MOFA is that Takeshima was incorporated peacefully, before Japanese aggression toward Korea had started. In reality, by the time Japan’s military annexed Takeshima in 1905, Japanese had already made serious inroads towards colonizing Korea. Much of Chosun’s independence had already been seriously degraded. As shown by U.S. Foreign Affairs records, Korea became militarily occupied by Japanese forces in Feburary 1904 and lost the ability to conduct foreign relations indepently in August of the same year.

A falsehood perpetuated by Japan’s MOFA is that Takeshima was incorporated peacefully, before Japanese aggression toward Korea had started. In reality, by the time Japan’s military annexed Takeshima in 1905, Japanese had already made serious inroads towards colonizing Korea. Much of Chosun’s independence had already been seriously degraded. As shown by U.S. Foreign Affairs records, Korea became militarily occupied by Japanese forces in Feburary 1904 and lost the ability to conduct foreign relations indepently in August of the same year.

To the right, a political cartoon of the day brilliantly depicts Korea’s situation at the time. Chosun attempts to stay neutral while Japan and Russia prepare for war over their desire to control Korea and the adjacent territory.

The Russo-Japanese War begins: On the night of February 8th 1904, the Japanese fleet under Admiral Heihachiro Togo opened the Russo-Japanese War with a surprise topedo attack on the Russian ships at Port Arthur and badly damaged two battleships. On the same day cheering Japanese residents watched a Japanese Naval squadron-one armored cruiser, five light cruisers, and eight torpedo boats-bombard two Russian warships off Palmido Island at the mouth of Incheon Harbor in Korea.

The protocol signed on February 23 1904, allowed the Japanese to occupy stragetegic areas of Korea to achieve the territorial integrity of Korea if endangered by the aggression of a third Power or internal disturbances.

The protocol signed on February 23 1904, allowed the Japanese to occupy stragetegic areas of Korea to achieve the territorial integrity of Korea if endangered by the aggression of a third Power or internal disturbances.

To forestall any backtracking Hayashi arranged to remove all chief anti-Japanese leaders from Korea. Thus, as of February 23, 1904 about a year before the Japanese annexed Dokdo, the Japanese were “legally” allowed to place their troops anywhere in Korea. As explained, even before the formal establishment of a protectorate in Korea, the Japanese were making de facto inroads on Korean sovereignty.

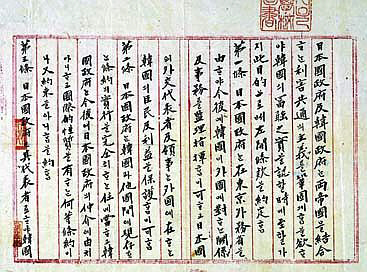

To the right is a photograph of Japanese Generals and Officials after signing the Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty

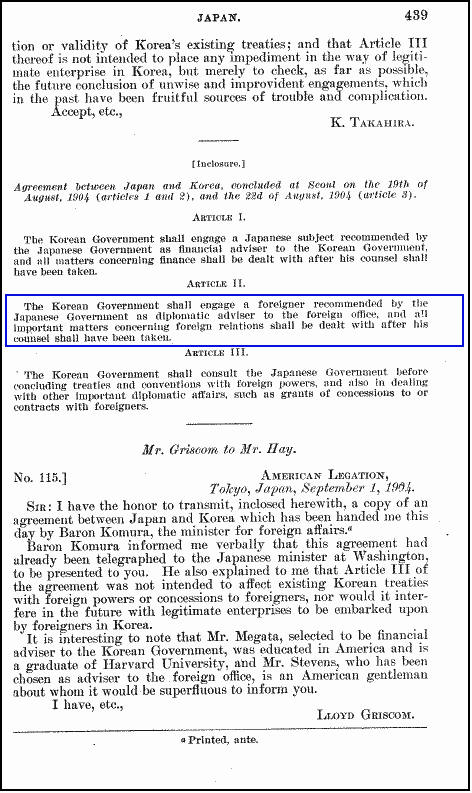

Article III:

“…Japan possessing paramount political, military and economic interests in Korea, Great Britain recognizes the right of Japan to take such measures of guidance, control and protection in Korea as she may deem proper and necessary to safeguard and advance those interests, provided always that such measures are not contrary to the principle of equal opportunities for the commerce and industry of all nations…..”

Note C:

“In case Japan finds it necessary to establish [a] protectorate over Corea in order to check [the] aggressive action of any third Power, and to prevent complications in connection with [the] foreign relations of Corea, Great Britain engages to support the action of Japan..”

After suffering heavy military losses in the Russo-Japanese War, Russia and Japan agreed to sign The Portsmouth Treaty. It was signed on September 5th 1905 and was mediated by Theodore Roosevelt.

After suffering heavy military losses in the Russo-Japanese War, Russia and Japan agreed to sign The Portsmouth Treaty. It was signed on September 5th 1905 and was mediated by Theodore Roosevelt.

The article relevant to Korea is as follows:

Article II

“…The Imperial Russian Government, acknowledging that Japan possesses in Korea paramount political, military and economical interests engages neither to obstruct nor interfere with measures for guidance, protection and control which the Imperial Government of Japan may find necessary to take in Korea…”

American foreign policy could be said to have favoured Japanese interests in Korea. As with the Portsmouth Treaty, the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki between China and Japan, supported Japanese involvement in Korea. Both of these treaties were drafted under American guidance.

No documents granting full powers to Japan have ever been found yet in any archives.

Article 1. “…The Government of Japan, through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Tokyo, will hereafter have control and direction of the external relations and affairs of Korea, and the diplomatic and consular representatives of Japan will have charge of the subjects and interests of Korea in other countries..”

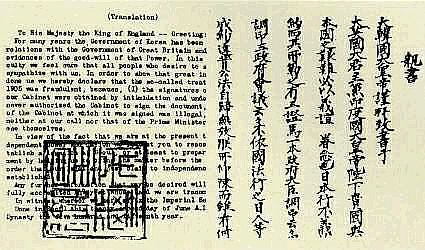

As we can see, it was through Article 1 of the coerced Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty that Korea lost the means to file protests beyond the internal government level. Upon refusing to sign the 1905 Protectorate Treaty, King Kojong issued a Declaration of Denial. The king sent a special envoy, Ambassador Young-Chan Min, the resident ambassador to the U.S. Secretary of State to Washington.

He also requested Homer B. Hulbert, a Missionary-Diplomat and longtime resident of Korea to convey his “Declaration of Denial” to the President of the United States (Roosevelt). However he was not allowed to present his protest.. He was advised he had no credentials from the existing government of Korea, i.e. the government imposed by Japan.

“…I the Emperor of the Korean Empire, declare that this Korea-Japan Agreement has no legal effect because this was concluded unlawfully by force. I did not sign the document and I will never sign it…”

The last months 1905 saw a flurry of Japanese diplomatic activity related to Korea with no less than four major agreements being completed. All of the Japanese treaties had special articles included for the sole purpose of stripping away Korea’s sovereignty. When one notes the timing of the agreements it becomes clear why the Japanese didn’t notify Korea of the annexing of Dokdo until one year after the fact (March 28, 1906).

The last months 1905 saw a flurry of Japanese diplomatic activity related to Korea with no less than four major agreements being completed. All of the Japanese treaties had special articles included for the sole purpose of stripping away Korea’s sovereignty. When one notes the timing of the agreements it becomes clear why the Japanese didn’t notify Korea of the annexing of Dokdo until one year after the fact (March 28, 1906).

By the time the Koreans became aware of the annexation of Dokdo, their Foreign Ministry had been dismantled. With this action, the abilty for them to file formal protests at a state-to-state level was lost.

To the right, this newspaper article was printed on January 1st 1930 in the Dong-Ah Ilbo’s Special New Year’s Addition.In this interview former Prime Minister Han Kyu-sul described in detail how the Japanese coerced and intimidated Korean officials who opposed the Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty. He testifies how tense the atmosphere became as Japanese soldiers surrounded the King’s quarters and forced the document to be signed.

Harvard Law school would later cite the Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty as one of four classic examples of a coerced treaty likening the agreement to HIlter’s coercion over European countries.

Over the years more documents have surfaced proving Japan’s real motives for seizing Dokdo during were seriously flawed. Thus, the Japanese Foreign Affairs Department has craftily tried to sanitize the Dokdo issue by claiming this is simply a territorial land dispute. Japanese historians make no mention of documented objections by Koreans who were shocked to know Japan had seized Dokdo Island (link) This is a deliberate effort to conceal the documented historical facts surrounding Japan’s military ambitions in Korea during this painful chapter of Asian history.